Data Lake vs. Data Lakehouse – Architecting the Modern Stack

1. TL;DR: Data Lake vs Data Lakehouse

For the last decade, architects were forced into a binary choice: the flexibility of the Data Lake or the reliability of the Data Warehouse. The Data Lake provided a low-cost, scalable repository for unstructured data, but it often devolved into a "swamp"—a chaotic dumping ground where data integrity was optional, and consistency was a myth.

The Data Lakehouse resolves this architectural dilemma. It is not a new storage engine; it is a new management paradigm.

By injecting a robust Metadata Layer (via open table formats like Apache Iceberg or Delta Lake) on top of standard cloud object storage, the Lakehouse brings ACID transactions, schema enforcement, and time travel to your raw data files. It eliminates the fragility of the "Schema-on-Read" approach.

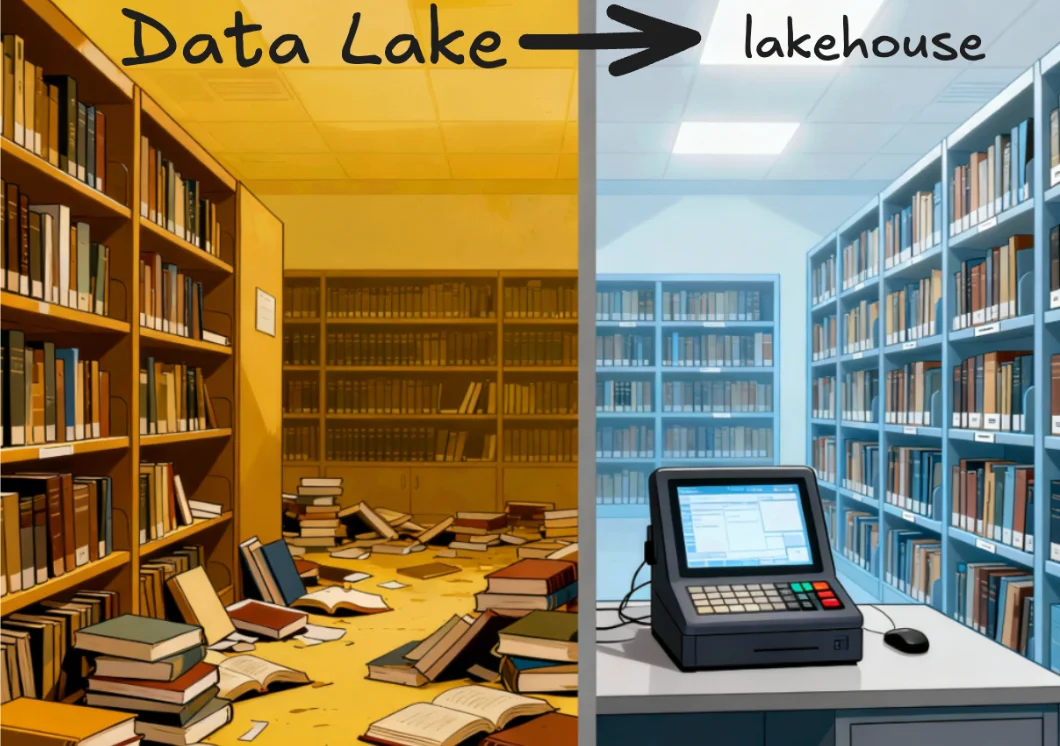

Let's make this concrete. Think of a traditional Data Lake like a massive library with no card catalog. The books (data) are all there, but finding a specific book requires walking every aisle.

The Data Lakehouse keeps the books on those same low-cost shelves but installs a state-of-the-art digital inventory system. You get the massive scale of the library with the precision, versioning, and security of a bank vault. The Data Lake gave us scale. The Data Lakehouse makes that scale governable.

Below is the technical cheat sheet defining the structural differences between a raw Data Lake and the modern Lakehouse architecture.

| Feature | Data Lake (The "Swamp") | Data Lakehouse (The Modern Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Storage | Cloud Object Storage (S3, ADLS, GCS) | Cloud Object Storage (S3, ADLS, GCS) |

| The Mechanism | Directory & File Listings | The Metadata Layer (Manifests/Logs) |

| Transaction Support | None | ACID Compliant |

| Schema Handling | Schema-on-Read which is fragile and prone to drift | Schema enforcement is robust and explicitly evolved |

| Updates/Deletes | Involves rewriting full partitions | Surgical with row-level update and delete capabilities |

| Performance | Slow (Listing thousands of files) | Optimized (Data skipping, Z-Ordering) |

2. An Introduction

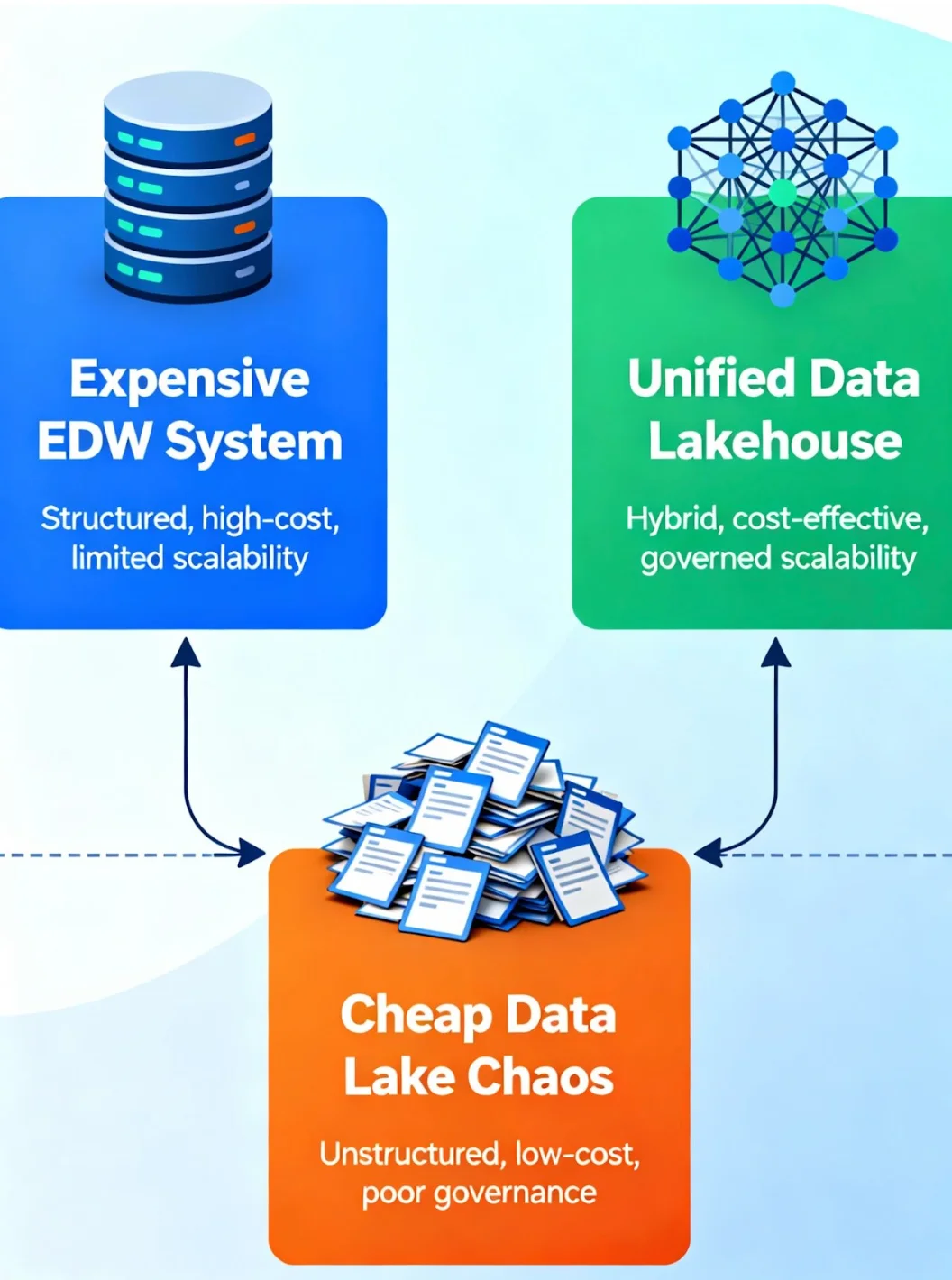

Modern data architecture has long been paralyzed by a fundamental compromise: the forced separation of cheap, vast storage (the Data Lake) from consistent, reliable storage (the Data Warehouse). This split gave rise to the "Two-Tier" architecture—a brittle hybrid of Data Lakes and Data Warehouses glued together by complex ETL pipelines. Before we can appreciate the solution, we must audit the cost of this complexity and understand why the industry reached its breaking point.

2.1 The Historical Context

To understand the Lakehouse, we must first dissect the architectural compromise that dominated the last decade. In the beginning, there was the Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW). These systems (e.g., Teradata, Oracle) were robust, strictly governed, and incredibly fast for SQL analytics. However, they were also rigid, exorbitantly expensive, and incapable of handling the explosion of unstructured data (logs, images, JSON) that defined the Big Data era.

Then came the pendulum swing to the Data Lake (Hadoop HDFS, then S3, GCS and ADLS). This solved the storage cost problem. We could dump petabytes of raw data into cheap object storage without worrying about structure. But this created a new problem: The Data Swamp. Without strict schema enforcement or ACID transactions, data quality degraded immediately upon ingestion.

The result was the "Two-Tier" architecture. Companies realized they couldn't run reliable BI on the Lake, and they couldn't afford to store everything in the Warehouse. So, they kept both.

2.2 The Business Friction

The Two-Tier architecture is functionally sound but operationally brittle. It forces organizations to maintain two fundamentally different systems to answer the same questions.

The Engineering Tax: Data Engineers are forced to become "high-paid plumbers", spending the majority of their cycles building and patching brittle ETL/ELT pipelines that move data from the Lake to the Warehouse.

The Staleness Gap: Because moving data takes time, the Warehouse is always behind. The BI team is analyzing yesterday's news, while the Data Scientists in the Lake are working with real-time but potentially "dirty" data.

The Consistency Nightmare: When a metric is defined differently in the Lake's raw files than in the Warehouse's curated tables, truth becomes subjective.

The industry accepted this complexity as the "cost of doing business". The Lakehouse architecture rejects this premise. It asks a simple question: Why move the data at all?

2.3 The Rise of Open Table Formats

The Lakehouse wasn't possible five years ago. The missing link was a technology that could impose order on the chaos of object storage without sacrificing its flexibility.

That link arrived in the form of Open Table Formats: Apache Iceberg, Delta Lake, and Apache Hudi.

These technologies did not reinvent storage; S3 is still S3. Instead, they reinvented how we track that storage. They introduced a standardized Metadata Layer that sits between the compute engine and the raw files. This layer acts as the "brain", handling transaction logs and schema definitions, effectively tricking the compute engine into treating a bunch of raw Parquet files like a structured database table.

The Shift: We moved from "Managing Files" to "Managing Tables". This was the catalyst. By bringing Warehouse-grade reliability to Lake-grade storage, the need for the "retail boutique" (the separate Data Warehouse) evaporates. You can now serve high performance BI directly from the lakehouse.

3. Background & Evolution

Innovation in data architecture rarely happens in a vacuum; it is almost always a reaction to failure. The journey to the Lakehouse wasn't a straight line—it was a rescue mission. We spent years drowning in the complexity of unmanaged object storage before realizing that cheap scale without governance is a liability, not an asset. To appreciate the solution, we must trace the steps that led us from the chaotic freedom of the Data Lake to the structured discipline of the Lakehouse.

3.1 The Data Lake Era

Before we reached the Lakehouse, we had to survive the Data Lake. This era was defined by the shift from expensive, proprietary hardware to commodity cloud object storage like Amazon S3, ADLS, and GCS. The philosophy was simple: store now, model later.

This approach, known as Schema-on-Read, was liberating but dangerous. It treated data ingestion like a dragnet—everything was captured, regardless of format or quality. You didn't need to define a table structure before saving a file. You just dumped the JSON, CSV, or Parquet blobs into a directory and walked away.

The fatal flaw with this approach was that, while storage was cheap, retrieval was expensive—not in dollars, but in human effort. Because the storage layer enforced no rules, the logic had to live in the application code. Every time a Data Scientist wanted to read a dataset, they had to write complex code to handle missing columns, corrupt files, and mismatched data types.

3.2 The Paradigm Shift

The industry reached a breaking point. We realized that files on a distributed file system were too primitive to serve as a reliable database. The breakthrough came when engineers stopped trying to fix the file system and instead built a brain on top of it.

This is the Metadata Layer.

In a traditional Data Lake, the "source of truth" is the file listing. If you want to know what data exists, you list the directory (e.g., ls /data/orders). In the modern Lakehouse, the Metadata Layer is the source of truth. The system ignores the physical files unless they are registered in a transaction log.

This decoupling is revolutionary. By separating the physical files from the logical table state, we unlocked ACID transactions on object storage. We moved from "eventual consistency" (where files might show up seconds later) to "strong consistency" (where a transaction is either committed or it isn't).

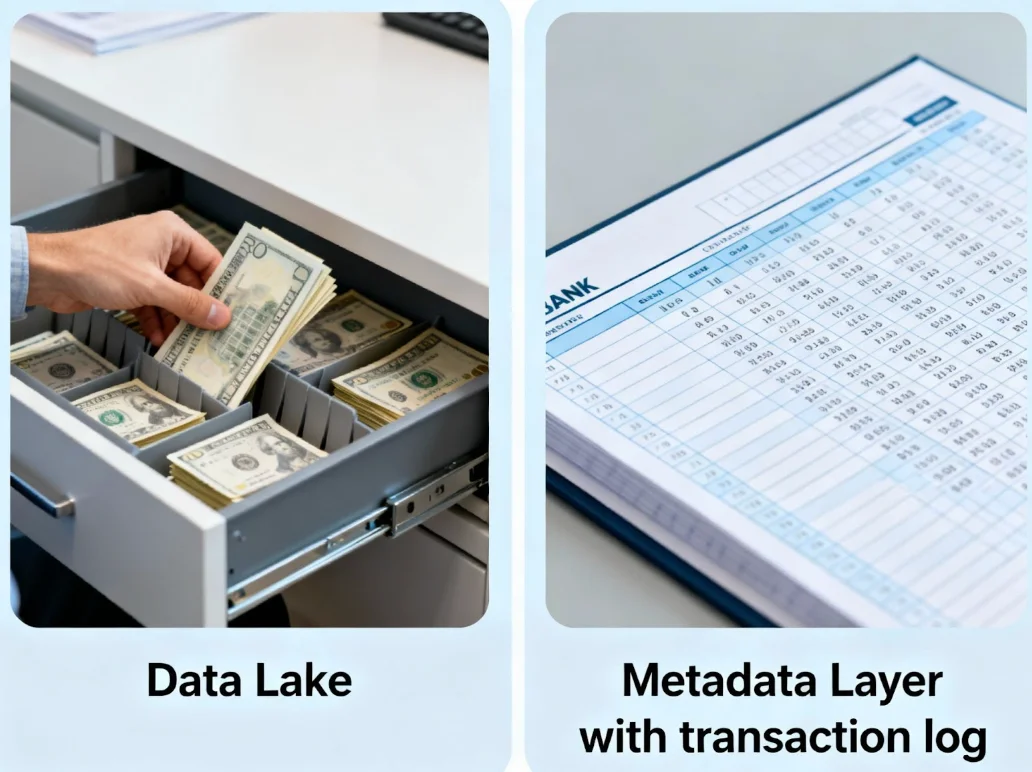

The Analogy: Think of this like Bank Ledger vs. Cash Drawer.

The Data Lake (Cash Drawer): To know how much money you have, you have to physically count every bill in the drawer. If someone drops a bill while you are counting, your number is wrong.

The Metadata Layer (Bank Ledger): You never count the cash. You look at the ledger. The ledger records every deposit and withdrawal. If the money is in the drawer but not in the ledger, it doesn't exist. It's only when the entry is made in the ledger that we take the money into account!

3.3 The Data Lakehouse Defined

So, what is a Data Lakehouse? It is not a specific software product you buy; it is an architectural pattern you implement.

A Data Lakehouse is a data management architecture that implements Data Warehouse features (ACID transactions, schema enforcement, BI support) directly on top of Data Lake storage (low-cost, open-format object stores).

It eliminates the technical debt of the "Two-Tier" system. You no longer need a separate warehouse for BI and a separate lake for low-cost storage. You have a single, unified tier where data is stored in an open format (like Parquet) but managed with the rigor of a relational database.

To say it metamorphically: The Data Warehouse was a walled garden. The Data Lake was a wild jungle. The Lakehouse is a managed park—open to everyone, but carefully landscaped and maintained.

4. Architectural Foundations: Under the Hood

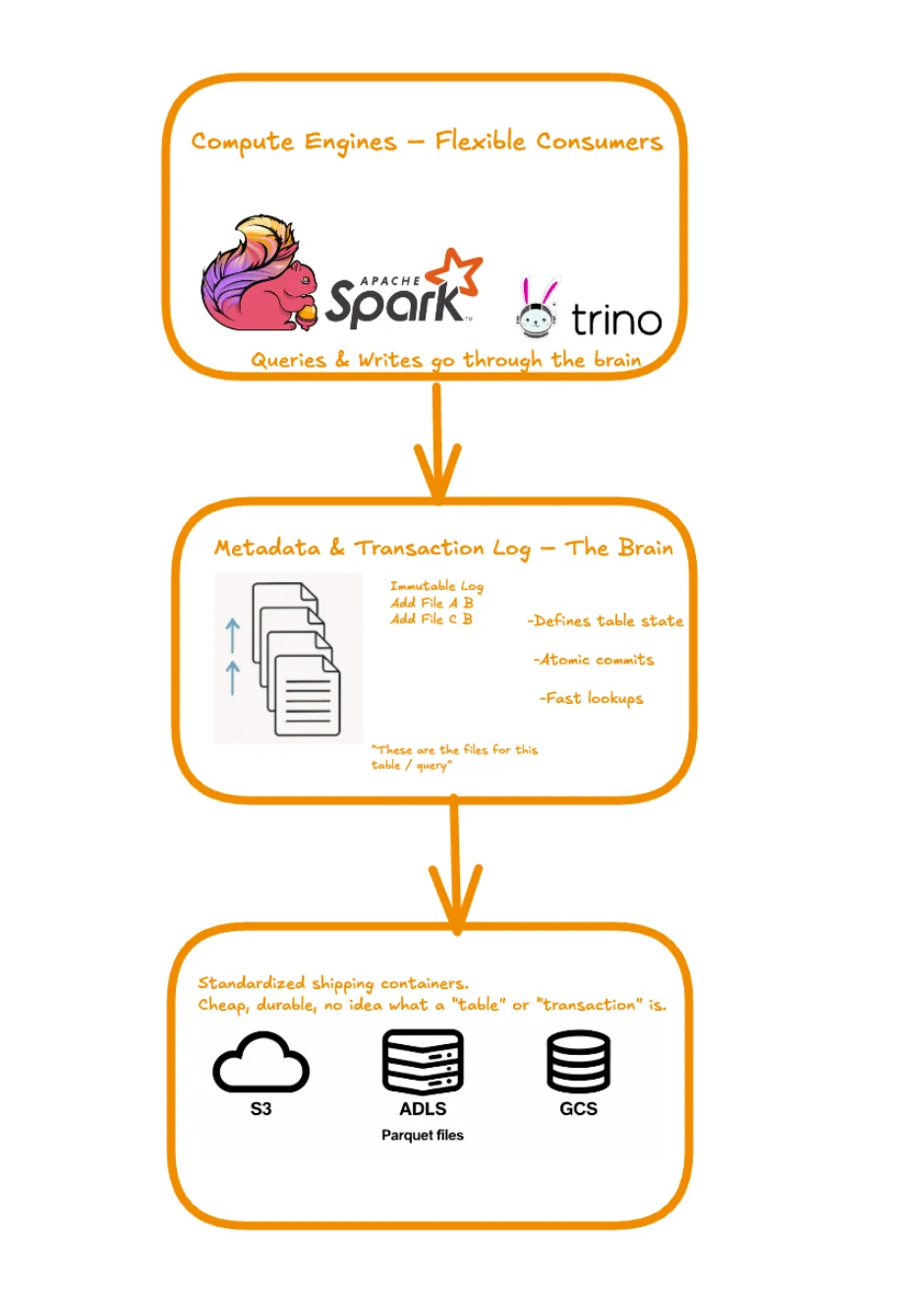

To the casual observer, a Data Lakehouse looks suspiciously like a Data Lake. Both live on S3 or ADLS, and both store data in Parquet files. So, where is the revolution? It isn't visible in the storage bucket; it's hidden in the control logic. To truly trust this architecture, we must lift the hood and inspect the three distinct layers that allow it to function: the Storage, the Metadata, and the Compute.

4.1 Storage Layer Dynamics: The "Dumb" Container

At the absolute bottom of the stack lies the physical storage layer. This is your standard cloud object store (AWS S3, Azure Data Lake Storage, Google Cloud Storage).

Crucially, the Lakehouse does not require proprietary storage. It utilizes open, distinct file formats—most commonly Apache Parquet, Avro, or ORC. These are columnar formats optimized for analytics, capable of high compression and efficient scanning.

In this architecture, the storage layer is intentionally "dumb". It has one job: store blob objects reliably and cheaply. It does not know what a "table" is. It does not know what a "transaction" is. It just holds the bytes.

Think of the Parquet files in S3 as standardized shipping containers. They are tough, stackable, and efficient at holding goods (data). But a shipping container doesn't know its destination or its contents. Without a manifest, it's just a metal box lost in a yard.

4.2 The Metadata & Transaction Log: The "Brain"

This is the most critical component. In a traditional Data Lake, the "state" of a table was determined by the file system itself. If you wanted to read a table, the engine had to list all the files in a directory. This was slow (S3 LIST operations are expensive) and unreliable (eventual consistency).

The Lakehouse replaces this directory listing with a Transaction Log (e.g., the _delta_log folder in Delta Lake or the Snapshot files in Iceberg).

This log is an immutable record of every single action taken on the table. When you write data, you don't just drop a file in a bucket; you append an entry to the log saying, "I added File A." When you delete data, you add an entry saying, "I removed File B."

Why is this game-changing?

Atomicity: The database sees the data only after the log entry is written. No more partial reads from half-written files.

Speed: The engine reads the small log file to find the data, rather than scanning millions of files in the storage bucket.

Let's understand this with the help of an example. Imagine you are looking for a specific patient's record in a hospital.

The Old Way (Data Lake): You have to walk room to room (directory listing), shelf to shelf (file listing), checking every file to see if it is the patient's file. It takes hours.

The New Way (Lakehouse): You check the Master Admission Log at the front desk. It tells you exactly which room and which shelf the patient's file is in. You go straight there. The Log is the source of truth, not the rooms.

4.3 Decoupled Compute Engines: The Flexible Consumers

Because the data (Parquet files) and the metadata (Logs) are open standards, the compute layer is fully decoupled. This means you can use different engines for different workloads on the same data without moving it.

- Spark can handle heavy batch processing (ETL).

- Trino (formerly PrestoSQL) can handle interactive, low-latency SQL queries.

- Flink can handle real-time streaming.

These engines no longer interact with the raw storage blindly. They interact with the Metadata Layer. When a query arrives, the engine consults the transaction log to perform Metadata Pruning—identifying exactly which files contain the relevant data and ignoring the rest before it even touches S3.

In the old world, the database owned the storage. In the Lakehouse, the storage owns itself, and the database engines (compute engines) are just renters.

5. Feature Showdown

Philosophy is useful, but features run production systems. The shift from Data Lake to Data Lakehouse isn't just about abstract architecture; it is about solving the specific, day-to-day engineering nightmares that plague data teams. So let's move beyond architecture, and take a look at the features that Data Lakehouse has to offer. Here, we contrast the fragility of the traditional Lake against the robustness of the Lakehouse across four critical dimensions.

5.1 Transactional Integrity

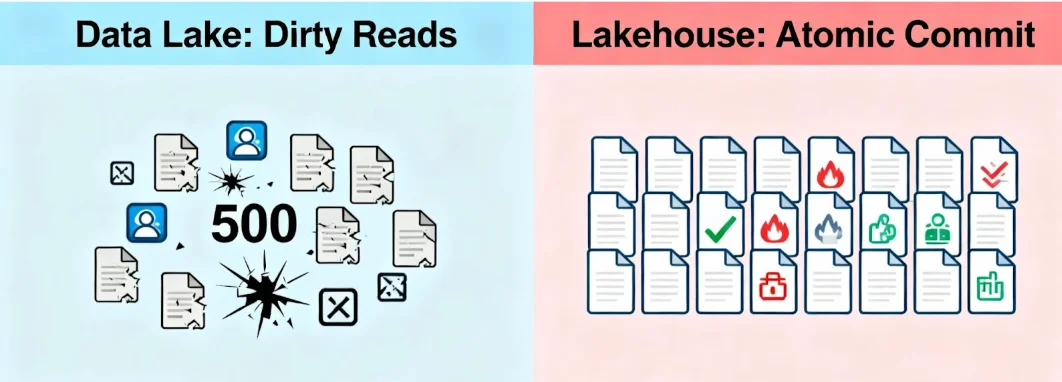

The single biggest risk in a traditional Data Lake is trust. Because object stores (like S3) are eventually consistent and operations are not atomic, a reading job can easily crash if it tries to read a dataset while a writing job is updating it.

The Lake Reality (The "Dirty Read" Zone): If a spark job fails halfway through writing 1,000 files, you are left with 500 "zombie" files in your directory. Your downstream dashboards ingest this partial data, reporting incorrect numbers. There is no "rollback" button; you have to manually identify and delete the corrupt files.

The Lakehouse Solution (Atomic Commits): The Lakehouse uses Optimistic Concurrency Control. When a job writes data, it stages the files first. The "commit" only happens when the Transaction Log is updated to point to these new files. This update is atomic—it happens instantaneously.

5.2 Schema Management & Evolution

"Schema-on-Read" was sold as flexibility, but in practice, it is often laziness. It pushes the burden of data quality onto the person reading the data, rather than the person writing it.

The Lake Reality (The "Drift" Nightmare): An upstream engineer changes a column from Integer to String without telling anyone. The nightly ETL pipeline crashes at 3:00 AM because the read-schema doesn't match the physical files. This is Data Drift.

The Lakehouse Solution (Enforcement on Write): The Metadata layer acts as a gatekeeper. If you try to append data that doesn't match the table's schema, the write is rejected immediately. However, it also supports Schema Evolution: you can explicitly command the table to merge the schema (e.g., adding a new column) without rewriting the entire history.

A Data Lake is a "Come as You Are" party. A Lakehouse has a strict "Dress Code", but the bouncer lets you change your outfit if you ask permission.

5.3 Performance Optimization

Data Lakes traditionally rely on Hive-style partitioning (e.g., date=2023-10-01) to speed up queries. This works for coarse filtering, but fails for granular queries.

The Lake Reality: If you want to find a specific customer_id within a massive daily partition, the engine has to scan every single file in that day's folder. This is an I/O bottleneck.

The Lakehouse Solution (Indexing & Skipping): The Metadata layer stores statistics (Min/Max values, Null counts) for every column in every file.

Data Skipping: The engine sees that the customer_id you want is 500, and File A's range for customer_id is 1-100. It skips File A entirely.

Z-Ordering: A technique that physically reorganizes data within files to co-locate related information, maximizing the effectiveness of data skipping.

Lets understand this with the help of an example. Imagine looking for a book in a library.

Partitioning: You know the book is in the "History" section (the folder), but you have to check every shelf in that section to get the desired book.

Z-Ordering/Skipping: You have the exact GPS coordinates of the book. You walk directly to the specific shelf and pick it up, ignoring 99% of the library.

5.4 Time Travel & Rollbacks

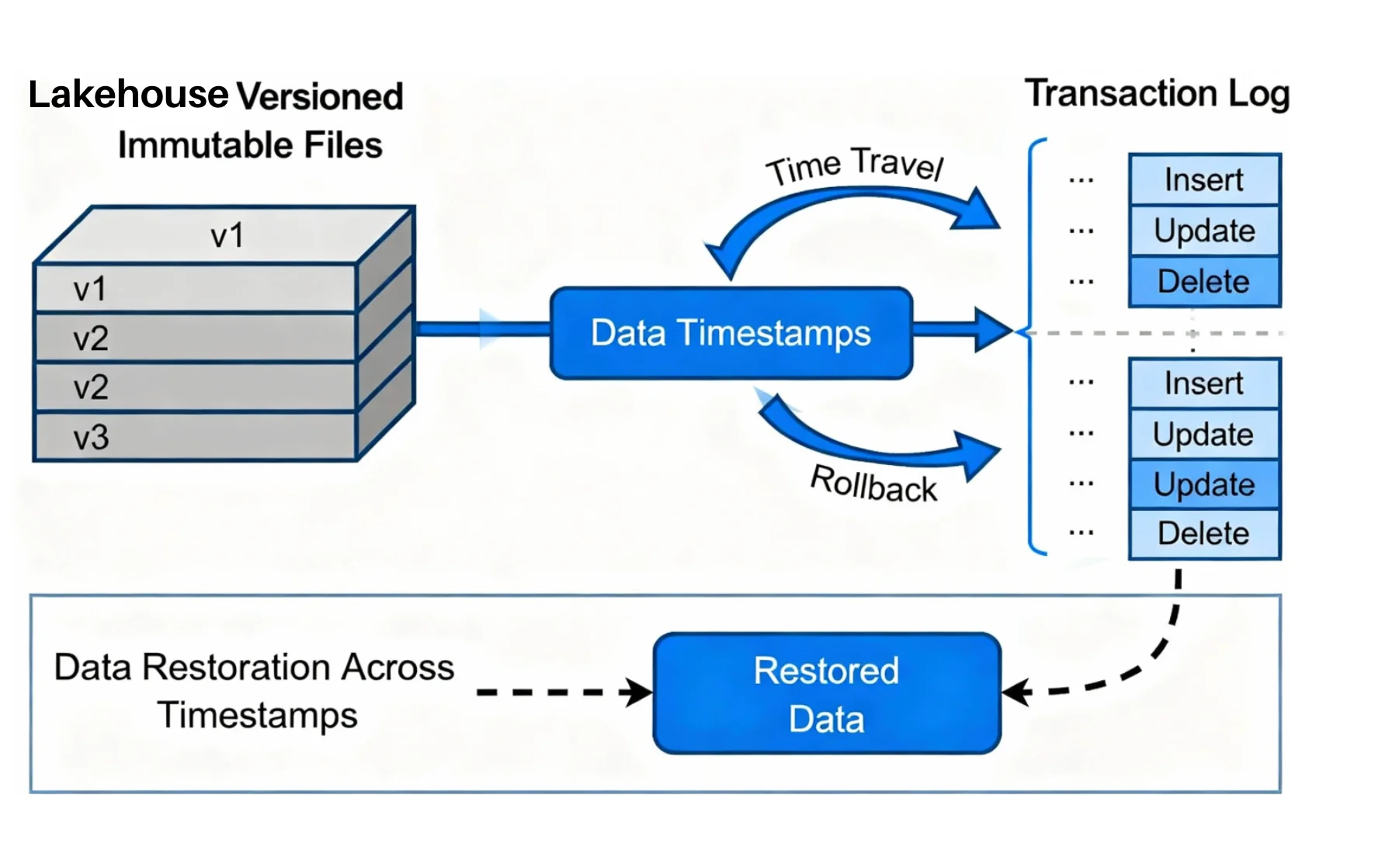

Because the Lakehouse uses immutable files and a transaction log, nothing is ever truly overwritten; it is simply "versioned out."

Every time you update a table, the log keeps the reference to the old files for a set retention period. This allows for Time Travel—querying the data exactly as it looked at a specific timestamp.

Did you accidentally delete the Sales table? In a Data Lake, it's gone forever. In a Lakehouse, you run a simple RESTORE command to revert the table to version n-1.

6. Real-World Workflows

In architecture, "one size fits all" is a dangerous lie. While the Data Lakehouse is a superior evolution for structured data management, it does not render the traditional Data Lake obsolete. The hallmark of a Pragmatic Architect is knowing when to use a scalpel and when to use a sledgehammer.

To design an efficient stack, we must delineate the boundaries. We need to identify where the raw, ungoverned nature of a Lake is actually an asset, and where the disciplined structure of a Lakehouse is a necessity.

6.1 Ideal Use Cases for a Pure Data Lake

The traditional Data Lake remains the champion of ingestion and unstructured storage.

The Raw Landing Zone (Bronze Layer): When data first arrives from IoT sensors or web logs, speed is paramount. You don't want to reject a critical log file just because it has a malformed header. Here, "Schema-on-Read" is a feature, not a bug. You dump the data first and ask questions later.

Unstructured Media: Images, video files, audio recordings, and PDF documents gain little benefit from ACID transactions or columnar pruning. They are binary blobs. A standard object store is the most cost-effective repository for this content.

Data Science Sandboxes: Sometimes, Data Scientists need a "playground" to experiment with third-party datasets or temporary scraps of code. Enforcing strict schemas here hinders innovation. Let them work in the messy garage if they want to, before forcing them into the clean lab.

Think of the Data Lake as the Loading Dock of a factory. It's messy, noisy, and full of unopened boxes. You wouldn't invite a customer (Business Analyst) here, but you absolutely need it to receive raw materials efficiently.

6.2 Ideal Use Cases for a Data Lakehouse

The Lakehouse shines the moment data needs to be consumed, trusted, or iterated upon. It becomes the default standard for the "Silver" (Curated) and "Gold" (Aggregated) layers of the Medallion Architecture.

High-Concurrency BI & Reporting: If you are pointing Tableau, PowerBI, or Looker directly at cloud storage, you must use a Lakehouse. Without it, your dashboards will be sluggish (due to listing files) and potentially inaccurate (due to eventual consistency). The Lakehouse provides the speed and reliability of a Warehouse at a fraction of the cost.

Production MLOps & Reproducibility: In a raw Lake, if a model trained yesterday starts failing today, debugging is impossible because the underlying data has likely changed or been overwritten. With a Lakehouse, you have Time Travel. You can query the data exactly as it existed at the specific timestamp of training (SELECT * FROM data VERSION AS OF '2025-10-31'). This guarantees 100% reproducibility for audits and debugging.

Regulatory Compliance (GDPR/CCPA): This is one of the killer use-cases. If a user requests the "Right to be Forgotten", you must find and delete their specific records. In a Data Lake, this requires rewriting massive partitions of data. In a Lakehouse, you execute a standard SQL DELETE FROM table WHERE user_id = '123', and the transaction log handles the rest surgically.

Use the Lake to catch the data. Use the Lakehouse to serve the data.

7. Strategic Selection

Architecture is the art of trade-offs. A successful architect does not chase the "newest" thing; they chase the "right" thing for the specific constraint at hand. While the Data Lakehouse is the modern standard, migrating to it is a non-trivial investment of engineering cycles.

Use the decision framework to determine if your organization actually requires the architectural rigor of a Lakehouse, or if a simple Data Lake is sufficient.

7.1 The Decision Framework

Do not guess. Analyze your workload against these three critical vectors. The choice isn't about which technology is better, but which one aligns with your data gravity.

| Vector | Data Lake | Data Lakehouse |

|---|---|---|

| Data Mutability | Append-Only. You rarely, if ever, update existing records. Data is treated as immutable logs (e.g., IoT telemetry, Clickstream). | High Churn. You need to handle frequent updates (CDC), row-level deletes, or privacy requests. The data is a living entity. |

| Consumer Profile | Engineers (Python/Scala). Consumers are comfortable handling file paths, dirty data, and schema mismatch in code. | Analysts (SQL). Consumers expect a "Table" abstraction. They write SQL and expect the engine to handle the complexity of files. |

| Governance & Compliance | Internal/Experimental. Data is for internal R&D. If a file is lost or a read is dirty, it is an annoyance, not a lawsuit. | Regulatory/Production. Strict audit trails, reproducibility, and exactness are required by law or SLA. |

The Architect's Heuristic:

Stick with the Data Lake if: Your primary goal is high-throughput ingestion of immutable data, and your consumers are sophisticated engineers who can handle "dirty" reads.

Adopt the Lakehouse if: You have any requirement for Updates (mutability) or SQL Analytics. Attempting to build an update-heavy SQL platform on a raw Data Lake is an anti-pattern that leads to brittle, unmaintainable code.

7.2 Pre-Migration Checklist

If you have decided to adopt a Lakehouse architecture, do not start coding immediately. Failures in Lakehouse implementations usually stem from environmental mismatches, not the format itself.

Verify these four items before your first commit:

Compute Compatibility Audit:

- The Question: Does your existing query engine (e.g., Trino, Spark, Flink) support the specific version of the table format (Iceberg v3, Delta 4.0) you plan to use?

- The Trap: Using a bleeding-edge Iceberg feature that your managed Athena or EMR instance doesn't support yet.

The Catalog Strategy:

- The Question: Where will the metadata live? (AWS Glue, Hive Metastore, Unity Catalog, Nessie?)

- The Trap: Splitting state between two catalogs. Ensure one catalog is the "Gold Standard" for identifying where tables reside.

Migration "Stop-Loss":

- The Question: Do we have a "hard cutover" plan or a "dual-write" plan?

- The Trap: Running the old ETL pipeline and the new Lakehouse pipeline in parallel for too long. They will diverge. Set a strict deadline to kill the legacy pipeline.

Vacuum Policy Definition:

- The Question: How many days of history do we keep?

- The Trap: Forgetting to configure automated cleanup (e.g., VACUUM in Delta). Without this, your storage costs will balloon as you retain years of "time travel" data that you no longer need.

A Data Lakehouse solves the software problems (ACID support, schema evolution), but it exposes the operational problems (Catalogs, Compatibility). Plan for the plumbing, not just the shiny features.

8. The Migration Strategy

Migrating a live data platform is not a singular event; it is a delicate structural renovation performed on an occupied building. You cannot simply evict your users to swap out the plumbing. We do not "switch" to a Lakehouse; we evolve into one.

The goal of this playbook is to demystify the transition. We need to move from the wild west of the Data Lake to the governed city of the Lakehouse without causing downtime or data loss. This is not a "lift and shift" operation; it is a "lift and structure" operation.

8.1 Pre-Migration Audit

You cannot govern what you cannot see. Before running a single migration command, you must audit the existing Data Lake to identify the "Swamp Zones"—areas where data quality has already degraded.

Format Inventory: Scan your object storage buckets. Are you dealing with pure Parquet? Or is there a mix of different file formats? Lakehouse converters (like CONVERT TO DELTA) work best on Parquet. Non-columnar formats will require a full rewrite (ETL), not just a metadata conversion.

Partition Health Check: Look for data skewness. Do you have some partitions with 1GB of data and others with 1KB? Migrating a poorly partitioned table into a Lakehouse just gives you a poorly partitioned Lakehouse table. Such datasets are not a good fit for in-place conversions.

The "Small File" Scan: Identify directories containing thousands of files smaller than 1MB. These are performance killers. You must flag these for compaction during the migration.

Do not rush this phase. A Lakehouse built on top of a swamp is still a swamp—just one with a transaction log. Identifying and fixing these structural weaknesses before you apply the metadata layer is the only way to ensure your new architecture actually performs better than the old one.

8.2 Migration Paths

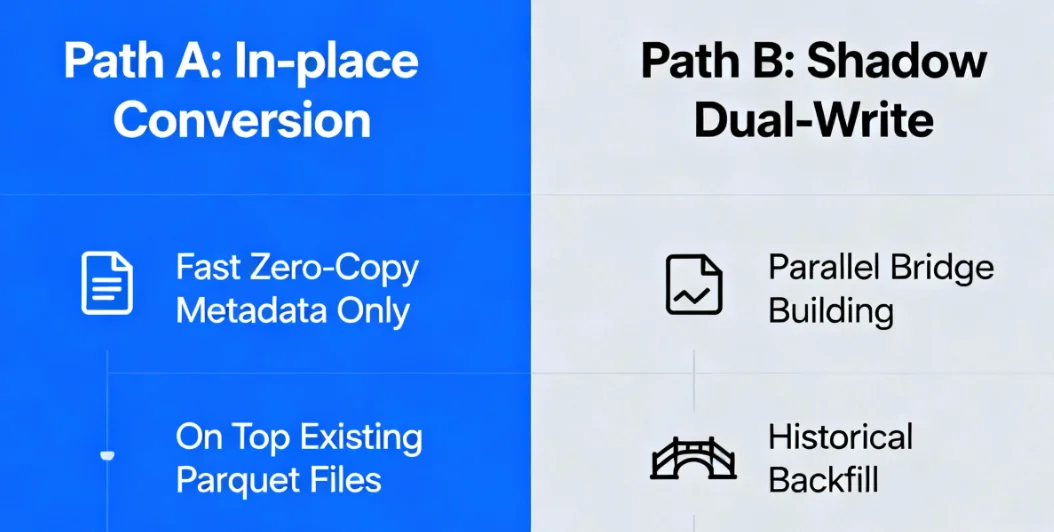

There are two distinct strategies for moving data into a Lakehouse format. The right choice depends on your tolerance for risk versus your need for speed.

Path A: In-Place Conversion (The "Zero-Copy" Method)

This is the superpower of modern table formats. Because Delta Lake and Iceberg often use the same underlying Parquet files as your existing Data Lake, you don't need to move the data. You simply generate the Metadata Layer on top of it.

In this strategy, you run a command like CONVERT TO DELTA or Iceberg's migrate procedure. The engine scans your existing Parquet files and writes a corresponding Transaction Log.

Pros: Incredibly fast; zero data duplication; low cost.

Cons: Inherits existing file fragmentation; requires the source data to already be in Parquet.

To have some analogy with the real world, this is like changing the deed to a house. You verify ownership and register it with the city (the Catalog), but you don't actually move the house or its furniture. The house stays exactly where it is, but its legal status changes instantly.

Path B: Shadow Dual-Write (The Safe Route)

For mission-critical tables (e.g., financial reporting), "instant conversion" is too risky. You need to prove the new system works before cutting over, which requires handling both the future and the past.

You configure your ingestion jobs to write to both the old Data Lake path and the new Lakehouse table simultaneously. This ensures all new data is captured in the new format.

While the streams are running, you launch a background batch job to read the historical data from the old Lake and INSERT it into the Lakehouse table. It is crucial that you define a precise "Cutover Timestamp". The backfill loads everything before this timestamp, and the dual-write handles everything after it. This prevents duplicate records at the seam where the two datasets meet.

You let the dual-ingestion run side-by-side for a week or so, comparing the output row-for-row. Once the Lakehouse table is proven accurate, you deprecate the old path.

Pros: Zero risk; allows for "cleaning" data during the write; guarantees correctness.

Cons: Double storage cost; double compute cost during the transition.

Think of this like building a new bridge parallel to an old one. You don't demolish the old bridge immediately. You build the new structure, route test traffic over it, and ensure it holds the load. Only when the new bridge is certified safe do you divert the public and dismantle the old one.

8.3 Common Pitfalls

Even with a perfect plan, the environment can trip you up. Watch out for these two specific traps.

The "Small Files" Hangover

If you convert a streaming Data Lake directly to a Lakehouse without compaction, the Metadata Layer will struggle to track millions of tiny files. The Transaction Log itself will become huge, slowing down queries.

One of the fixes for this "small files" issue is to run a compaction job immediately after conversion (the compaction job on the raw lake might not be as efficient as the one on the data lakehouse) to merge those tiny files into reliable 128MB-1GB chunks.

The "Split Brain" Catalog

Your Spark jobs think the table is in the Lakehouse (using the Transaction Log), but your Hive Metastore thinks it's still a raw directory.

In order to prevent this, ensure your Catalog Sync is configured correctly. When you update the Lakehouse table, the changes must propagate to the Metastore so that tools like Trino or Presto can see the new schema immediately.

In summary, migration is not about moving data; it is about moving the source of truth. Once the transaction log is established, the raw files are no longer the authority—the Log is.

9. Performance & Cost Tuning

A common misconception is that the Lakehouse is "set it and forget it". It is not! While the architecture abstracts away much of the complexity, it relies on physical file management to maintain performance.

If you treat a Lakehouse exactly like a raw Data Lake—dumping files endlessly without maintenance—you will eventually hit a performance cliff. Queries will slow down, and storage costs will balloon. A good data architect understands that a high-performing Lakehouse requires a rigorous hygiene routine.

9.1 Optimization Strategies

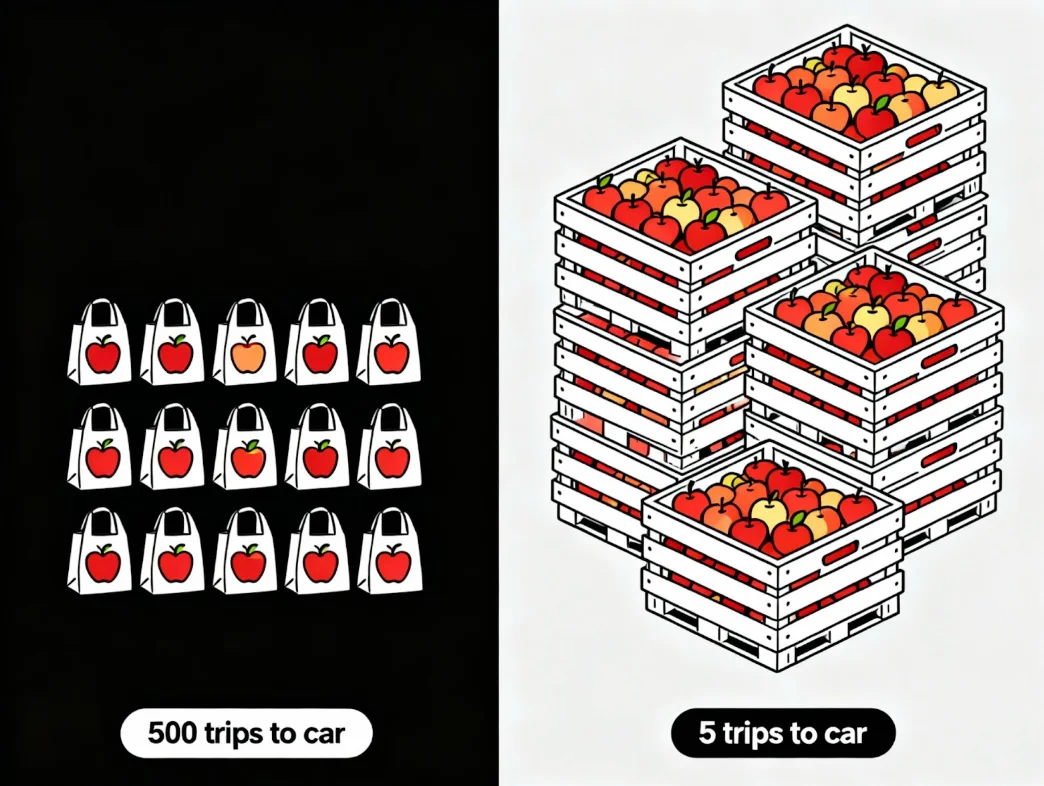

The greatest enemy of performance in cloud object storage is not data volume; it is file quantity. Every time your query engine reads a file from S3 or ADLS, there is a fixed overhead for each file. If you stream data in real-time, you might generate millions of tiny 10KB files per day. When a user runs a query, the engine wastes 90% of its time just opening and closing each small file, not reading data. This is commonly known as the small files problem.

The solution to this problem is compaction (bin-packing). You must schedule regular maintenance jobs (e.g., OPTIMIZE in Delta or rewrite_data_files in Iceberg). These jobs read the small, fragmented files and rewrite them into larger, contiguous files (optimally 128MB to 1GB).

Think of this like unloading groceries.

Unoptimized (Small Files): You have 500 tiny bags, each containing one apple. You have to walk back and forth to the car 500 times. It takes all day.

Optimized (Compacted): You have 5 large crates containing all the apples. You make 5 trips. You are done in minutes.

9.2 Storage Hygiene

One of the Lakehouse's best features—Time Travel—is also its most expensive liability if left unchecked.

When you overwrite a table, the Lakehouse doesn't delete the old data; it simply marks it as "obsolete" in the Transaction Log but keeps the physical files for version history. If you update a 1TB table daily and keep all history, after 30 days, you aren't paying for 1TB; you are paying for 30TB of storage.

The solution to this problem is Vacuum & Retention Policies. You must aggressively manage your retention window. Use commands like VACUUM to physically delete files that are no longer referenced by the latest snapshot and are older than your retention threshold (e.g., 7 days).

Think of your storage bucket like a corporate filing cabinet:

Without Vacuum: You keep every draft, every typo, and every duplicate version of every document you've ever written. Eventually, you have to buy a second building just to store the paper.

With Vacuum: You have a shredder. You keep the final contract and the previous draft for safety. Everything else gets destroyed after a week.

Overall, performance is not just about faster code; it is about fewer files. Cost control is not just about cheaper storage; it is about deleting what you don't need.

10. Some FAQs

In every architectural review, there comes a moment when the whiteboard is full, but the stakeholders still have lingering doubts. These are the "Elephants in the Room"—the questions that often go unasked until it is too late. Let's tackle the most common friction points you might encounter while considering Data Lake vs Data Lakehouse.

10.1 Is the Data Lake dead?

No. The Data Lake is not dead; it has simply been demoted. The era of the Data Lake as the primary serving layer for analytics is over. However, as a landing zone for raw ingestion and a repository for unstructured data (video, audio, logs), it remains unbeatable in terms of cost and throughput. The Lakehouse does not kill the Lake; it wraps a protective layer around it to make it civilized.

10.2 Can I use Snowflake/BigQuery as a Lakehouse?

Yes, but with caveats. Originally, Snowflake and BigQuery were distinct Data Warehouses that required you to load data into their proprietary storage. Today, both have evolved. They now offer features (like External Tables or BigLake) that allow them to query open formats, like Parquet, sitting in your own S3 buckets.

The Difference: A "Pure" Lakehouse (like Trino/Iceberg stack) is open by default. A "Warehouse-turned-Lakehouse" is often a proprietary engine reaching out to open storage. The architecture is similar, but the vendor lock-in dynamics differ.

10.3 Does Lakehouse replace Data Warehouse and OLAP?

You must distinguish between "Reporting" and "Serving."

Does it replace the Data Warehouse (Reporting)? Yes, for most use cases. If your goal is internal BI (Tableau/PowerBI) where a query taking 5 seconds is acceptable, the Lakehouse is more than capable. The days of needing a separate Teradata or Redshift instance just for daily reporting are over. However, for customer facing data, data warehouses are still a preferred choice.

Does it replace Real-Time OLAP (Serving)? No. If you are building "User-Facing Analytics" (e.g., a "Who Viewed My Profile" feature on a website) where thousands of concurrent users expect sub-second latency, the Lakehouse is too slow. For this, you still need a specialized Real-Time OLAP engine (like ClickHouse, Apache Pinot, or Apache Druid) reading from the Lakehouse.

The Lakehouse retires the Warehouse, but it feeds the OLAP engine.

11. Conclusion

We have spent the last decade treating Data Lakes and Data Warehouses as rival siblings—one cheap and messy, the other expensive and strict. We built elaborate pipelines to keep them talking, wasting millions of engineering hours on the transportation of data rather than the analysis of it. The Data Lakehouse ends this rivalry. It is not a compromise; it is a unification.

By injecting a Metadata Layer into the storage tier, the Lakehouse validates the original promise of Big Data: that we could keep everything forever and query it reliably. We no longer need to choose between the infinite scale of the Lake and the transactional trust of the Warehouse; we get both, without the overhead of moving data between them.

The path forward is not to tear down your infrastructure, but to evolve it: keep the raw Data Lake for your landing zones (Bronze), but strictly enforce Lakehouse standards for your curated layers (Silver & Gold). For too long, Data Engineers have acted as movers, carting bytes from one silo to another. The Lakehouse allows us to stop being movers and start being builders.

Stop moving the data, start managing the state!

Ready to build your Data Lakehouse? OLake helps you replicate data from operational databases directly to Apache Iceberg tables, providing the foundation for a modern lakehouse architecture. Check out the GitHub repository and join the Slack community to get started.

OLake

Achieve 5x speed data replication to Lakehouse format with OLake, our open source platform for efficient, quick and scalable big data ingestion for real-time analytics.