Data Warehouse vs Data Lakehouse - Architecting the Modern Stack

1. TL;DR: Data Warehouse vs Data Lakehouse

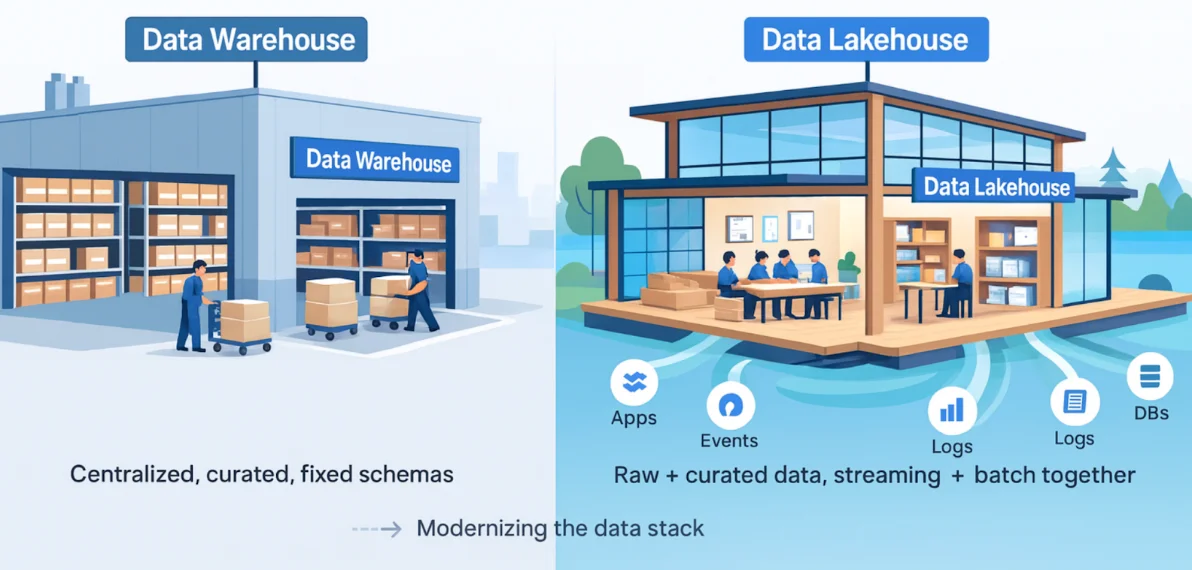

The debate is over the monopoly on reliability and governance. Historically, the Data Warehouse (DW) offered these features—ACID transactions, rigid security, and integrated BI performance—but demanded a high-cost model and forced data into proprietary formats. This is precisely where the Data Lakehouse (LH) redefined the game. It uses open table formats (like Iceberg or Delta Lake) to augment the low-cost, flexible storage of the data lake, achieving the same mission-critical data management capabilities previously exclusive to the DW. The Data Warehouse remains superior for specific, high-concurrency BI serving, but the Data Lakehouse is the future-proof architecture for unifying all batch, streaming, BI, and AI workloads, handling both structured and unstructured data on a single, open data copy.

Below is the technical cheat sheet defining the major differences between a Data Warehouse and the modern Data Lakehouse architecture.

| Criterion | Data Warehouse (DW) | Data Lakehouse (LH) | Critical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Storage | Proprietary and tightly coupled | Cloud Object Storage (S3/ADLS/GCS) | Cost and Portability: DW cost is high, LH cost is commodity. |

| Data Modality | Optimized for Structured data | Handles Structured, Semi-Structured, Unstructured | Flexibility: LH unlocks AI/ML use cases directly on raw data. |

| Schema Evolution | Strict Enforcement (Often DDL required) | Flexible/Managed (Evolution without full data rewrite) | Agility: LH avoids schema evolution nightmares. |

| ACID Transactions | Native and fully integrated | Enabled by Open Table Formats (Iceberg, Delta Lake) | Reliability: LH can now handle multi-statement updates reliably. |

| Cost Model | Primarily Compute (Query and Storage often bundled) | Primarily Storage (Compute is decoupled and variable) | Scale: LH is dramatically more cost-effective at Petabyte scale. |

| Vendor Lock-in | High (Proprietary formats and APIs) | Low (Open formats, multi-cloud ready) | Strategy: LH is the foundation for an open, future-proof data strategy. |

2. An Introduction

The evolution of modern data platforms is not a story of technological novelty, but a direct response to acute business friction and spiraling costs. The dual-architecture reality—Data Warehouse for BI and Data Lake for everything else—has created unacceptable operational overhead and latency. Our task as pragmatic architects is to construct an architecture that is simultaneously high-governance, cost-efficient, and inherently flexible. This section establishes the context for why the Data Lakehouse paradigm became an inevitable necessity.

2.1 The Historical Context

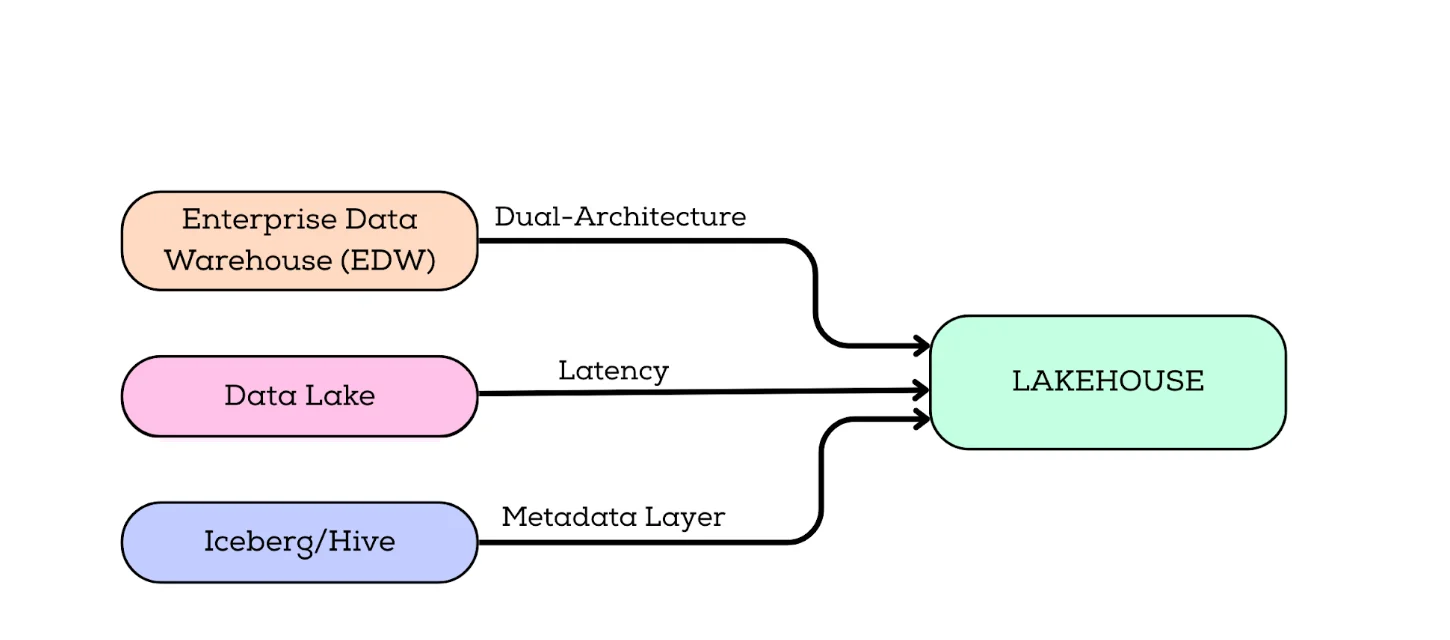

The Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW) was once the unchallenged monolith for critical reporting, excelling in rigid SQL environments demanding high governance. Yet, as the volume of unstructured and semi-structured data exploded, the EDW's high cost and lack of flexibility forced the creation of the Data Lake—a massive, cheap repository for raw files on object storage. This split created the fundamental dual-architecture challenge. To gain insights, data had to be moved, transformed, and validated between the Lake and the DW via complex ETL/ELT pipelines, a process that was brittle and highly bottlenecked. This constant copying resulted in redundant storage costs, massive operational overhead, and huge data latency. This environment of fragile pipelines created the pressure point, demanding a solution that could unify the low cost of the lake with the transactional reliability of the warehouse. The solutioning of this problem arrived with Hive/Hadoop, and then matured significantly with the Open Table Formats (like Apache Iceberg), which function as a governing metadata layer sitting on top of the cheap object storage. The Lakehouse was born to solve the cost and latency nightmare of the dual architecture.

2.2 Defining the Two Paradigms

The Data Warehouse Defined

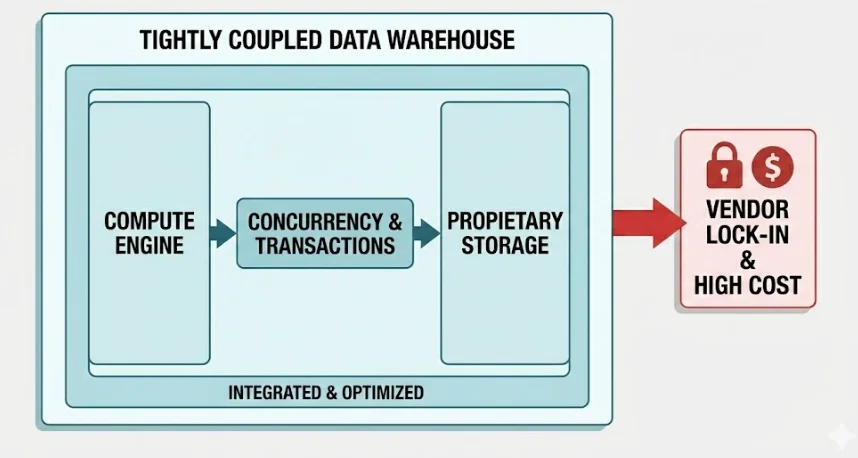

The Data Warehouse is fundamentally characterized by its tightly coupled architecture. Its compute engine, proprietary storage formats, and concurrency control are all integrated into a single, highly managed platform. This integration is intentional: the platform manages its internal data layout, using techniques like micro-partitioning and automatic indexing, solely to maximize performance for its dedicated query engine. The system guarantees high transactional integrity and immediate data consistency by virtue of this holistic control. The critical limitation, however, is that this architecture necessitates premium pricing and introduces significant vendor lock-in due to its proprietary nature.

The Data Lakehouse Defined

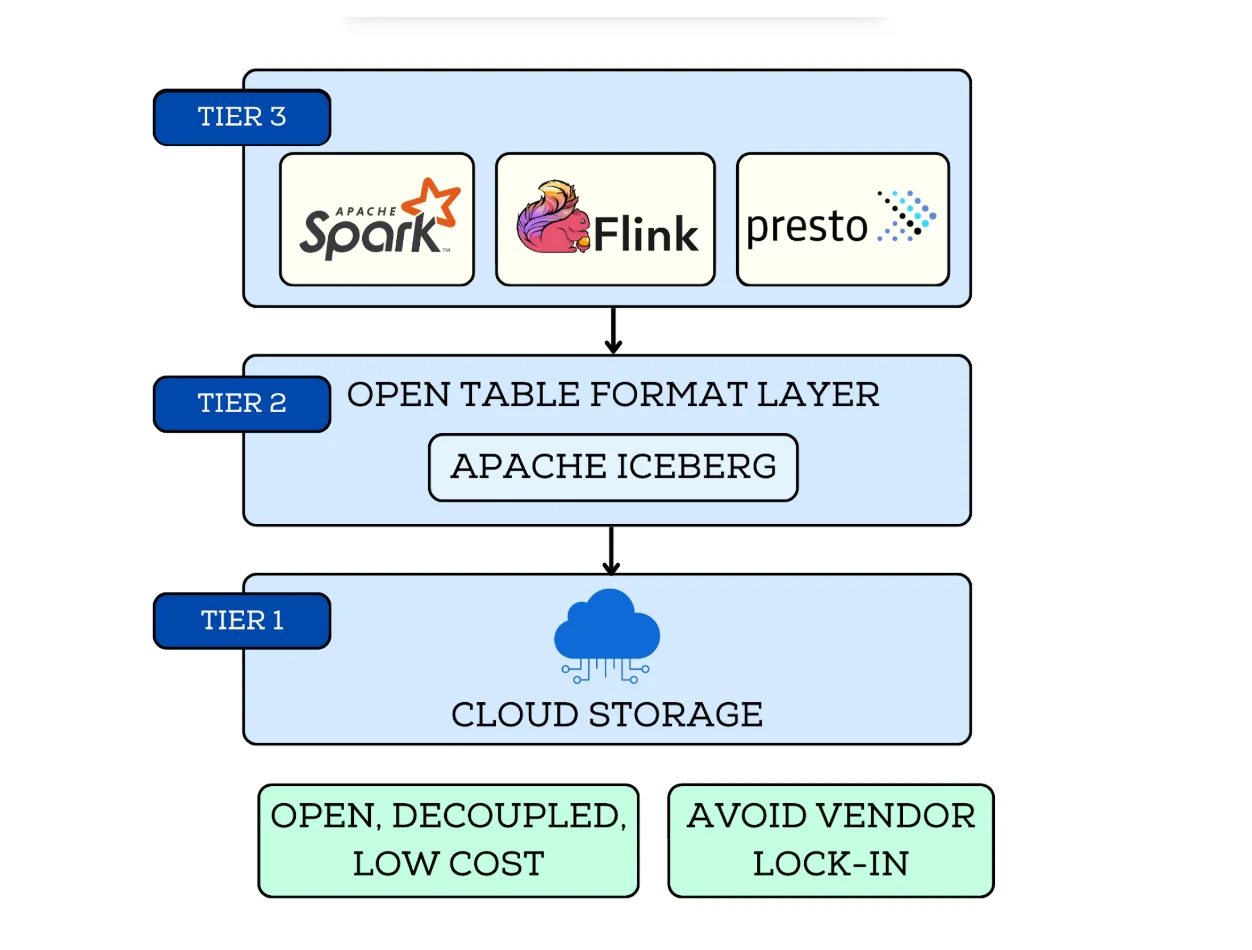

The Data Lakehouse is defined by its three-tier, decoupled architecture, which prioritizes openness, scalability, and cost efficiency.

The foundation, or Tier 1, is commodity cloud object storage (S3, ADLS, GCS), offering massive scale and the lowest cost per byte.

The critical innovation resides in Tier 2: the Open Table Format Layer (e.g., Apache Iceberg). This layer acts as the transaction manager, maintaining a verifiable, atomic record of all file states. This is the mechanism that enables ACID properties on inherently non-transactional object storage.

Analytics is executed by Tier 3: multiple, independent Decoupled Query Engines (Spark, Flink, etc.) that read the data using the open format's metadata. The Lakehouse uses optimistic concurrency control, where multiple writers can attempt transactions and resolve conflicts via the metadata log, ensuring consistency without proprietary locks. This decoupling ensures the data is future-proof and accessible by any tool; the Data Lakehouse maximizes strategic flexibility and minimizes risk of vendor lock-in.

3. Core Architectural Foundations

The strategic decision between a Data Warehouse and a Data Lakehouse is fundamentally an architectural one, rooted in how each system handles two critical layers: physical storage and metadata management. The differences here dictate everything from cost at scale to transactional reliability and vendor lock-in risk. We must systematically deconstruct how these two paradigms approach the fundamental challenges of data persistence and data state.

3.1 Storage and Data Layout Dynamics

Let's dissect the fundamental difference between these two paradigms: how they physically store and optimize the data itself.

Proprietary Storage: The Data Warehouse (DW)

The Data Warehouse relies on proprietary storage, meaning the file system and optimization mechanisms are internal, opaque, and tightly integrated with the query engine.

The DW automatically manages its internal data layout for optimal read performance. It employs techniques like micro-partitioning and clustering keys (defining the sort order) to ensure that the engine reads only the minimum amount of data required to answer a query.

Think of the DW's storage as an F1 Race Car. It is built for maximal, integrated performance. Every piece of the car is custom-designed to work with every other piece. You don't get to choose the components; you just interact with the highly optimized result. This integration guarantees speed and consistency, but its cost is premium, and the internal data is entirely inaccessible from outside the platform. High performance is assured, but portability is zero.

Open-Standard Storage: The Data Lakehouse (LH)

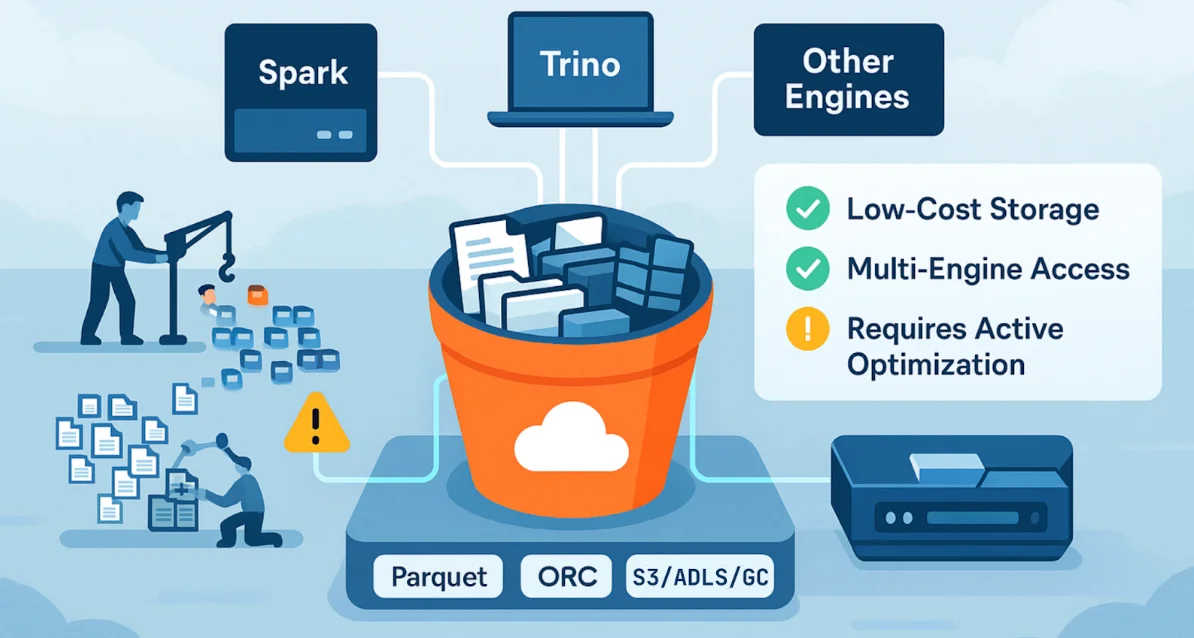

The Data Lakehouse stands in stark contrast by leveraging open-standard storage—namely, commodity cloud object storage (S3, ADLS, GCS) using open file formats like Parquet or ORC.

The storage is decoupled from the compute engine. The data resides as files in a low-cost bucket. Optimization is achieved by managing the size and organization of these files, often using techniques like partitioning (on columns like date or region) and ensuring file sizes are optimal (typically 128MB to 512MB) to avoid the "Small Files" nightmare that cripples Hadoop/Hive performance.

The LH gains massive cost savings and portability because the raw data is stored in standard, non-proprietary formats that can be accessed by any compute engine (Spark, Trino, etc.) across any cloud. The trade-off is that optimization is an explicit engineering task. If data ingestion results in millions of tiny files, the LH will perform poorly. The LH is flexible and cheap, but optimization requires active data engineering.

The choice hinges on two factors: cost and strategic flexibility. The DW provides superior, out-of-the-box performance because its storage is maximally optimized for its single query engine. The LH provides massive scale, dramatic cost reduction (paying commodity prices for storage), and zero vendor lock-in. The Data Warehouse delivers integrated power; the Data Lakehouse unlocks open architecture freedom.

3.2 Metadata, Catalog, and Transaction Management

The real measure of reliability in a data platform lies in its control plane: how it manages state, transactions, and schema. This is where the architectures diverge most dramatically.

The Integrated Control Plane (Data Warehouse)

In the Data Warehouse, the control plane is monolithic and hidden. The system maintains a proprietary, integrated catalog, a transaction log, and locking mechanisms internally.

The DW handles every aspect of the data lifecycle—schema definition, concurrency locking, and commit histories—as a single unit. When you execute a DML (Data Manipulation Language) statement, the internal mechanisms ensure immediate consistency by using traditional database locking.

Think of the DW's control plane as a bank vault's transaction ledger. Every operation is instantaneously recorded, validated, and applied sequentially by the same, singular authority. This ensures high transactional throughput and reliability, but you have no access to the underlying mechanics. Governance is seamless but proprietary.

The Decoupled Layer (Data Lakehouse)

The Data Lakehouse operates on the principle of decoupled reliability. Since the storage is dumb (S3/ADLS doesn't natively support transactions), the open table format must manage the state externally.

The core of the Lakehouse is the metadata layer, which maintains a transaction log or Manifests. This is not the data itself, but a complete record of every data file that constitutes the table at any given moment. A "snapshot" is essentially a pointer to a specific, consistent set of files.

The Lakehouse achieves reliability using optimistic concurrency control and snapshot isolation. When a job attempts a write, it reads the latest snapshot, performs its changes, and attempts to commit a new snapshot to the metadata store. If a conflict is detected (another job committed a change in the interim), the write is typically retried. This prevents corruption without requiring expensive, system-wide locks.

This metadata layer is like a version commit in a Git repository. The data files are the content. The Manifests/Snapshots are the commit history. You are never updating the files directly; you are committing a new, immutable version of the state of the table. This decoupling allows multiple compute engines to read and write reliably to the same single copy of data.

The DW provides transactional consistency through pessimistic locking in a proprietary, integrated system. The LH provides transactional consistency through optimistic concurrency control via an open, external metadata ledger. The DW guarantees reliability through proprietary control; the LH achieves reliability through open, managed metadata.

4. Feature Showdown

The real-world battle between the Data Warehouse and the Data Lakehouse is won or lost on specific feature capabilities. These features are not mere add-ons; they are the solutions to the most common enterprise data problems, such as integrating diverse data types, managing schema evolution, and optimizing query performance. We must compare these systems feature-by-feature to determine which architecture is truly future-proof against evolving business demands.

4.1 Data Modalities

The type of data a platform can ingest, process, and query reliably defines its utility in the modern enterprise. This is where the Lakehouse demonstrates an undeniable strategic advantage over the historical limitations of the Data Warehouse.

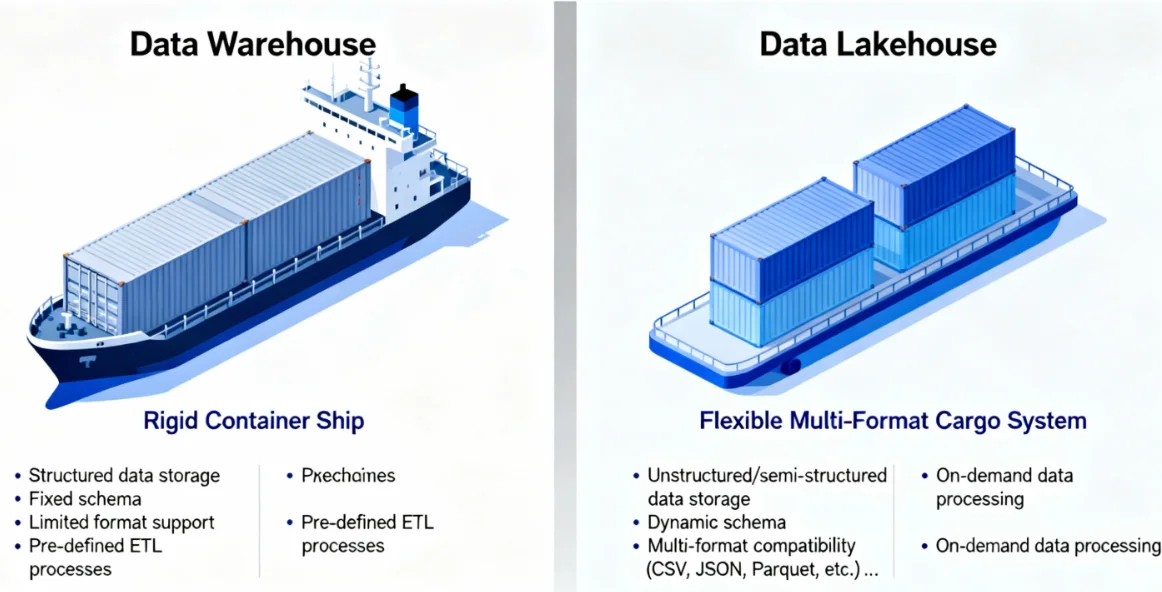

The Data Warehouse was engineered for structured data. This means rigid, defined-before-ingestion data that adheres to a precise schema, often normalized across multiple tables. Its power lies in its ability to enforce strict DDL (Data Definition Language) rules, ensuring data integrity for mission-critical BI (Business Intelligence) reporting and complex joins across highly normalized tables. The DW treats raw, semi-structured formats (like JSON or XML) as secondary types, often requiring them to be parsed and flattened into structured columns before they can be efficiently queried or joined.

The DW is like a highly specialized cargo ship designed only for standard-sized, perfectly packed containers. It's incredibly efficient for its specialized task, but rejects anything irregularly shaped. The DW guarantees order at the cost of excluding non-compliant data.

The Data Lakehouse, on the other hand, is designed for multi-structured data, seamlessly unifying all formats under one governing metadata layer. The LH's foundation on the Data Lake means it ingests raw, unstructured, and semi-structured data natively. The open table format (Apache Iceberg, Delta Lake, etc.) governs the data files regardless of whether they contain structured Parquet, raw image binaries, or dense JSON payloads. This capability is crucial for advanced analytics like AI/ML feature engineering, which frequently requires direct access to high-dimensional or raw data formats.

As an example, when using data on the lakehouse, a data scientist can run an Apache Spark job against the same Iceberg table that a BI tool queries. The table contains a structured column for user data and a column holding raw JSON event payloads. Both are managed atomically. The Data Lakehouse unlocks AI/ML use cases by eliminating the brittle pipeline needed to sanitize raw data before accessing it.

In conclusion, the DW forces raw data to conform to its structured requirements, leading to data loss and increased latency. The LH allows data to remain in its native format, ready for immediate consumption by any tool, whether SQL-based (for reporting) or Spark-based (for data science). The Data Warehouse enforces fragmentation; the Lakehouse achieves unification.

4.2 Schema Evolution

Data schemas are not static; they are dynamic, driven by application updates, new tracking requirements, and business logic shifts. A system's ability to handle these changes gracefully—without forcing downtime or complex ETL rewrites—is a measure of its future-proof design. This is where the Lakehouse fundamentally solves one of the most common bottlenecks of the traditional data pipeline.

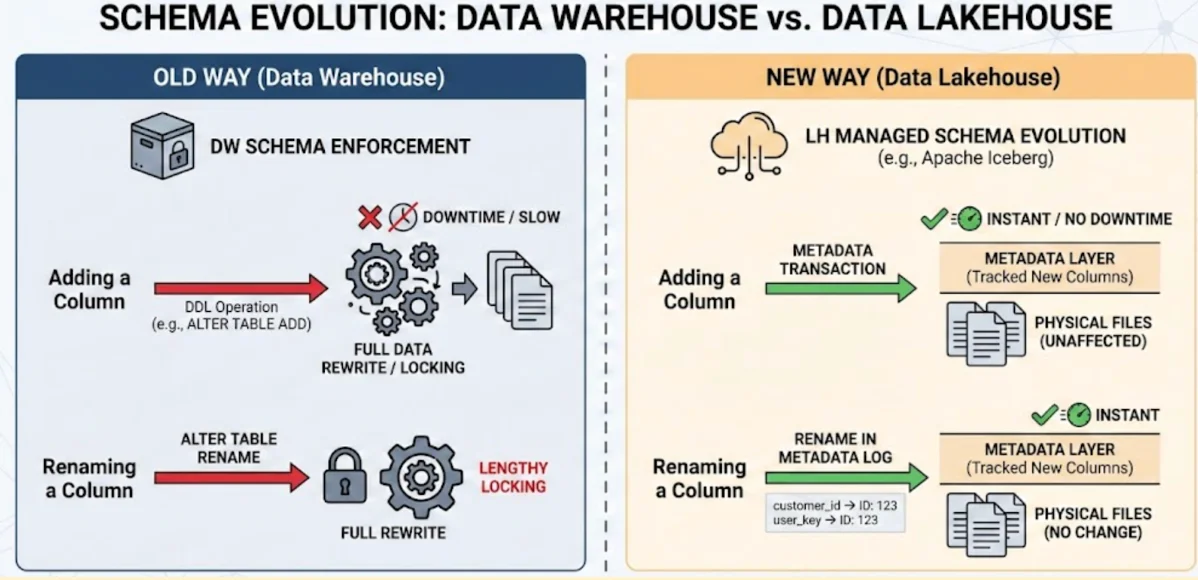

The Data Warehouse operates on a principle of Schema Enforcement: the data must conform to the schema defined in the DDL (Data Definition Language). Any change—adding a new non-nullable column, changing a column type, or renaming a field—often requires a mandatory, system-wide DDL operation and can necessitate a full rewrite of the data, especially if the change affects core sorting or partitioning. If data streams with a slightly updated schema, the DW typically rejects the entire batch, leading to a data ingestion nightmare.

The Data Lakehouse, utilizing open table formats like Apache Iceberg, enables managed schema evolution as a core feature. The format manages the schema at the metadata layer, not the file system layer. This allows for non-destructive schema changes:

Adding Columns: Trivial. New columns are simply tracked in the metadata; old files are unaffected and readers assign null values.

Renaming/Dropping Columns: Non-destructive and metadata-only. The physical data files are never rewritten. The new schema simply maps the new name to the same column ID.

Imagine renaming the column customer_id to user_key.

Old Way (DW): Execute ALTER TABLE RENAME COLUMN.... This may trigger a lengthy locking operation or even a full data rewrite in the background, consuming compute resources and slowing queries.

The New Way (LH): The Iceberg format records the rename in the table's metadata log. Since readers always look up columns by ID, not name, the physical data files do not change. The operation is instant. Schema evolution becomes a metadata transaction, not a data rewrite.

The LH transforms change management from a high-risk, data-centric operation into a low-risk, metadata-centric operation. The Data Lakehouse enables true schema flexibility without compromising data integrity.

4.3 Performance Optimization

While the Data Warehouse has long held the performance advantage, the Data Lakehouse has rapidly closed the gap by adopting sophisticated, managed metadata techniques. The fundamental difference lies in whether the optimization layer is proprietary and integrated or open and metadata-driven.

The DW employs a principle of integrated optimization where proprietary, deeply integrated techniques operate largely automatically, demanding minimal explicit user input beyond defining basic sort keys. The DW utilizes internal mechanisms to create and maintain indices and statistics, commonly referred to as clustering keys and zone maps, which are inherently coupled with the query execution engine. The primary benefit is that the system automatically determines the optimal physical layout, ensuring the engine accesses the smallest possible subset of data files to answer a query. This integrated approach guarantees low latency for predictable, structured BI workloads.

The DW is like an automating sorting machine in a massive fulfillment center; you drop the data in, and the machine internally arranges, indexes, and optimizes everything perfectly without human intervention. The DW abstracts optimization complexity at a premium cost.

The LH achieves performance optimization by storing detailed statistics and data pointers within the open table format's metadata, a strategy that enables highly efficient data skipping before the underlying files are even read. Key techniques involve the format (e.g., Iceberg) storing Min/Max statistics and other aggregated metrics (like Bloom Filters) within the snapshot or manifest files. When a query is executed, the query engine (Spark, Trino) only needs to read this lightweight metadata to determine precisely which data files are relevant. For example, if a query specifies WHERE order_date > '2023-10-01', the engine reads the metadata and immediately skips reading any file whose maximum date is less than the query date. While this approach is open, it does require explicit data engineering for optimal performance, notably through techniques like Z-Ordering (to improve clustering on multiple dimensions) and frequent file compaction to consolidate many small files into optimally sized ones, thereby avoiding the Small Files problem. The LH achieves performance efficiency through intelligent metadata and minimized I/O.

The DW's optimization is automatic and integrated; the LH's optimization is open, explicit, and driven by rich metadata, resulting in dramatic improvements in query planning and I/O efficiency. Metadata is the Data Lakehouse's secret weapon against sluggish query times.

4.4 Data Versioning

The ability to query data "as of" a past state, or to instantly revert a table to a prior version, moves beyond mere archival into the realm of reliable data governance. This capability, often called Time Travel, is non-negotiable for debugging pipelines, auditing, and recovering from human error.

In a traditional DW, versioning is often limited, costly, or implemented via separate proprietary features that demand specialized configuration. While modern cloud DWs may offer full database or cluster snapshots for disaster recovery, these are typically coarse-grained and not optimized for querying a specific table's state from three hours ago. Querying a specific historical point in time for a single table often requires relying on complex log files or manual backups, a process that is resource-intensive and slow.

In DW, performing an instant rollback from a bad merge or deletion is a major operational effort, often requiring reloading data from external staging areas. The DW treats historical state as a backup challenge, not a native query feature.

The Data Lakehouse enables native, lightweight, and cost-effective Time Travel by design, treating every write operation as a new, immutable version of the table. This is the direct result of the open table format's metadata management. Since every transaction generates a new, consistent snapshot in the metadata (which points to a new set of data files), the old snapshots are automatically preserved. The physical data files themselves are never overwritten, only logically retired.

Lets understand this with the help of an example. Say, a buggy ETL job runs at 2:00 PM and deletes all records for January.

Old Way (Traditional DW): To recover, a data engineer must locate the January data in an external backup, stop the current job, and re-ingest the data—a task taking hours and introducing risk.

The New Way (LH): The engineer immediately executes a simple command: ALTER TABLE table_name ROLLBACK TO SNAPSHOT_ID <ID_before_2PM>. Because the previous, correct metadata snapshot is still preserved and points to the original, undamaged data files, the table reverts instantly. Recovery becomes a metadata operation, not a massive data movement task.

The Lakehouse fundamentally changes data recovery from a tedious, high-risk operational task into a simple, metadata-driven query and commit. The Data Lakehouse makes irreversible data loss obsolete by design.

4.5 Data Security

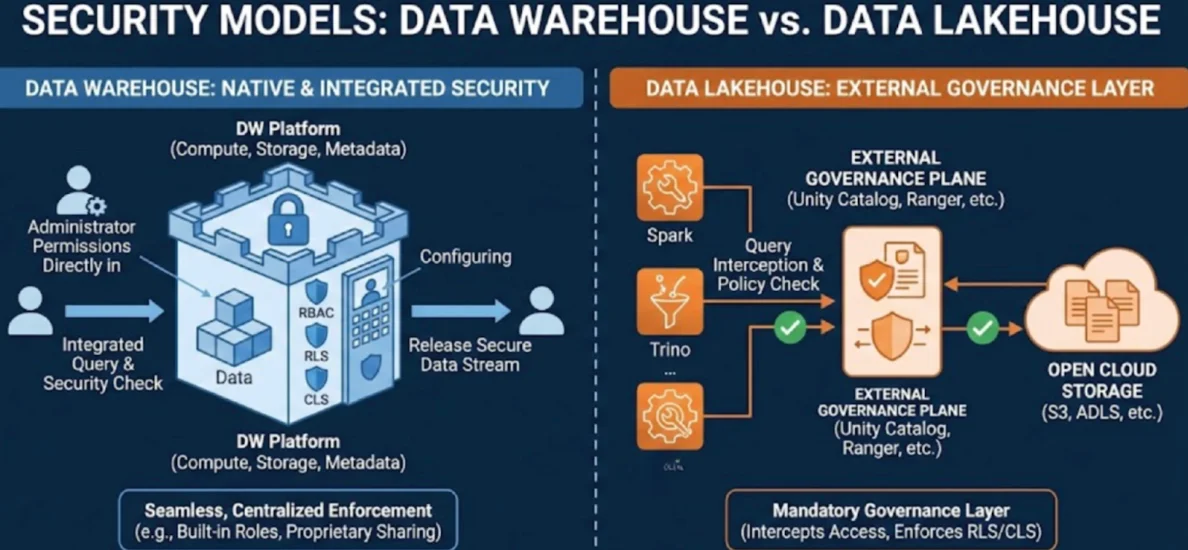

Security is non-negotiable, particularly when dealing with sensitive information subject to regulatory compliance. The critical divergence here is between a security model that is native and integrated versus one that is external and enforced via an added layer.

The Data Warehouse provides a security model that is robust, native, and highly integrated into the platform's core engine. DWs offer highly granular, native Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). Administrators define precise permissions for users and groups directly within the system—at the account, database, schema, table, or even row and column level. This simplicity and integration are powerful. Sharing data with external parties is often handled securely and natively through proprietary protocols (like Snowflake's Data Sharing or BigQuery's data exchange), which allow the consumer access without physically copying the data. Because compute, storage, and metadata are all tightly coupled, the platform guarantees that every access request is authenticated and authorized before the query runs. The DW guarantees security through seamless, centralized enforcement.

The Lakehouse, due to its decoupled nature, must rely on external governance layers to enforce security policies across multiple query engines. The data sits in open cloud storage (S3, ADLS, etc.), accessible by multiple compute engines (Spark, Trino, etc.). If a user bypasses the intended query engine and accesses the file system directly, no security policy is enforced by the table format itself. To achieve DW-level security, the LH requires a dedicated, centralized governance plane (like Unity Catalog, Apache Ranger, or proprietary vendor solutions). This layer intercepts queries from all engines and checks permissions against the central policy before allowing the engine to read the data files. This governance plane manages not just table permissions, but also Row-Level Security (RLS) and Column-Level Security (CLS).

The DW is like having security guards placed inside a locked vault. The LH is like storing your valuables in a self-storage unit but hiring a separate security concierge service to stand at the entrance and check the ID and manifest of every person who attempts to open any unit. The LH achieves security through necessary, centralized external governance.

The Data Warehouse excels with native, out-of-the-box security. The Data Lakehouse provides the same level of security, but requires an additional, mandatory governance tool or layer to bridge the gap created by its decoupled, open architecture. Security is guaranteed in both, but achieved via fundamentally different architectural patterns.

5. Real-World Workflows

The choice between the Data Warehouse and the Data Lakehouse is ultimately a decision guided by workload and business requirements, not just feature counts. A pragmatic architect does not seek a single winner but seeks the optimal tool for the job. This section defines the specific conditions under which each architecture achieves peak value.

5.1 Ideal Use Cases for the Data Warehouse

The Data Warehouse remains the definitive choice where sub-second latency and high concurrency are non-negotiable requirements, particularly for predictable, structured workloads. The DW is ideal for complex financial reporting where stringent, proprietary governance is mandated and the data volume is predictable. Its integrated architecture makes it the superior choice for high-SLA dashboards that serve thousands of concurrent business users who rely on stable query performance. In scenarios where the data team has low Data Engineering maturity and requires a fully managed, SQL-centric environment with minimal administrative overhead, the DW offers simplicity and assurance. The DW excels where consistency, integration, and established BI performance take precedence over cost and data format flexibility.

5.2 Ideal Use Cases for the Data Lakehouse

The Data Lakehouse (LH) is the clear winner when dealing with diverse data types, massive scale, and the need to unify analytical and machine learning processes. It is the optimal choice for unifying batch/streaming ingestion on a single, low-cost platform, eliminating the "dual-write" ETL problem. Data scientists require direct, fast access to raw, multi-structured data for complex ML/AI feature engineering and model training, a task perfectly suited to the LH's ability to govern raw files. Furthermore, if the organization requires open formats and demands multi-cloud portability to avoid vendor lock-in, the LH provides the architectural freedom needed for a future-proof strategy. The LH unlocks scale, flexibility, and advanced analytics by centralizing diverse workloads on an open data foundation.

5.3 The Unified Hybrid Architecture

For the most sophisticated enterprises, the final answer is often not "either/or" but "and". The Unified Hybrid Architecture leverages the Lakehouse as the primary staging and transformation platform and uses the DW only as the final serving layer. In this model, the Lakehouse manages the raw (Bronze) and refined (Silver) layers, handling schema evolution, massive transformations, and ML feature creation efficiently and cheaply. The finalized, highly denormalized, and aggregated Gold layer is then loaded into the Data Warehouse. This small, clean Gold layer within the DW is used only for high-performance BI serving. This structure combines the LH's cost efficiency and flexibility for data transformation with the DW's integrated speed and high concurrency for dashboard consumption. The hybrid model delivers the best of both worlds, using the Data Lakehouse for complexity and the Data Warehouse for speed.

6. The Decision Matrix

A good data architect does not guess; they evaluate. The final choice between the Data Warehouse and the Data Lakehouse must be made through a structured assessment of core business drivers and technical constraints. This matrix operationalizes that assessment, allowing you to weigh the trade-offs on criteria that directly impact total cost of ownership and long-term strategic flexibility.

| Decision Criteria | Choose Data Warehouse If... | Choose Data Lakehouse If... | Critical Impact/Cost Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Volume & Growth | Predictable, transactional, or T-shirt sized (e.g., up to tens of TB). | Massive, petabyte-scale or highly unpredictable growth profiles. | DW cost scales steeply with storage and proprietary compute. LH storage is commodity priced. |

| Workload Type | Predominantly sub-second BI/Reporting for a large, concurrent user base. | Highly diverse (Streaming ingestion, ML/AI feature engineering, Ad-hoc data exploration). | LH requires an external, optimized query engine (Trino, etc.) for DW-level sub-second BI. |

| Data Modality | Structured and highly normalized data is the sole focus. | Requires seamless integration of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data. | The DW forces complex, costly ETL to flatten and sanitize non-structured data. |

| Team Skillset | Team is primarily SQL Experts with low Data Engineering maturity. | Team is proficient in Spark/Python and possesses high Data Engineering maturity. | LH operational overhead is higher; it requires explicit file compaction and metadata management. |

| Regulatory & Governance | Compliance requires fully integrated, native RBAC and security with minimal third-party tools. | Compliance can be met using external governance layers (Unity Catalog, Apache Ranger) that manage permissions across decoupled components. | DW security is simpler out-of-the-box; LH requires the overhead of managing the governance layer. |

| Vendor Strategy | Strategy is defined by preference for a single, fully managed, integrated toolchain. | Demand for open formats, multi-cloud readiness, and freedom from vendor lock-in. | DW vendor lock-in risk is high because the data is stored in proprietary, inaccessible formats. |

The conclusion is definitive: prioritize the Data Warehouse for integrated BI speed and simplicity; prioritize the Data Lakehouse for scale, cost control, and strategic flexibility.

7. The Migration Playbook: Warehouse to Lakehouse

Successfully transitioning from a tightly integrated Data Warehouse environment to the open, decoupled world of the Data Lakehouse demands rigorous planning. This is not just a data movement exercise; it is a fundamental shift in governance and operational management. A good data architect must anticipate the specific friction points of this transition to ensure a reliable and governable outcome.

7.1 Pre-Implementation Assessment

Before initiating migration, a meticulous audit must quantify the existing vendor lock-in and proprietary dependencies in the Data Warehouse. The focus is identifying components that must be replaced by open-source or decoupled Lakehouse services.

Identify all non-standard, vendor-specific SQL functions or stored procedures that cannot be directly translated to standard Spark SQL or Python/PySpark. This is a common bottleneck that demands significant code rewrite.

Precisely document the existing DW's native Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and Row/Column-Level Security (RLS/CLS). These proprietary rules must be mapped one-to-one onto a new, centralized external governance layer (e.g., Unity Catalog or Apache Ranger) in the Lakehouse environment.

Quantify the current DW compute/storage scaling costs, using this figure to establish the immediate economic justification for migrating to the lower-cost, decoupled Lakehouse architecture.

7.2 Migration Paths

The primary challenge of this migration is decoupling the previously integrated storage and compute layers without creating brittle interim pipelines.

1. The Incremental Decoupling (Recommended Staged Approach): This is the most common and robust path. Start by establishing the Lakehouse on your object storage (S3/ADLS/GCS) using the chosen open format (Iceberg/Delta). Instead of rewriting all ETL, use the DW for the final Gold consumption layer, but rewrite the upstream staging (Bronze/Silver) pipelines to run on the Lakehouse. This allows the team to build Data Engineering maturity with the new architecture while the critical BI dashboards remain stable on the DW. The DW gradually shrinks to a high-performance serving cache.

2. Full ETL/ELT Rewrite (High Risk, Total Freedom): This involves a complete parallel build, rewriting all data movement and transformation logic (from ingestion to the final Gold layer) to run entirely on the Lakehouse compute (e.g., Spark/Trino). This provides the quickest path to eliminating the DW and achieving full architectural freedom, but demands high initial resources and poses the largest risk of downtime and data discrepancy if not meticulously validated.

3. ETL Offload (Cost Reduction Focus): The simplest strategy involves keeping the DW's storage intact but moving its heavy compute-intensive jobs (like complex transformations or data cleansing) to external Lakehouse compute engines. The results are written back to the DW. This is a temporary cost-reduction measure but does not address vendor lock-in or multi-structured data flexibility.

7.3 Common Pitfalls

Migrating from a highly managed DW to an open LH exposes new operational responsibilities that were previously automated.

The Small Files Problem: In the DW, file management was invisible. In the LH, if your ingestion pipelines (often Spark-based) create millions of files smaller than 128MB, it will cripple performance. You need to implement explicit file compaction jobs (often scheduled daily) to consolidate files into optimal sizes, directly managing the data layout for performance.

ACID Transaction Misunderstanding: Relying on the Lakehouse's optimistic concurrency control is different from the DW's pessimistic locking. Complex, long-running updates may lead to more transaction conflicts. You need to adjust job scheduling and transformation logic to minimize read/write contention, prioritizing small, atomic writes to maintain consistency.

Overlooking the Cost of Egress: While LH storage is cheap, moving large volumes of data out of your cloud object storage (Egress) to a different cloud or service can incur huge, unexpected costs. You need to design the architecture to keep compute co-located with storage and minimize unnecessary data movement across regions or clouds. Operational stability in the LH requires continuous, deliberate maintenance, a responsibility the DW previously handled silently.

8. Performance & Cost Tuning

The promise of the Data Lakehouse—high performance coupled with commodity storage costs—is only realized through deliberate, ongoing operational management. A pragmatic architect understands that performance in a decoupled system is a direct result of effective metadata management and file layout. This section provides the specific tuning strategies to maximize efficiency and govern spending.

8.1 Optimization Strategies

In the Data Lakehouse, performance optimization is achieved through active manipulation of the file structure and metadata to enable data skipping and efficient I/O.

Mandatory File Compaction: This is the most critical maintenance task. Ingestion, particularly streaming or micro-batch loads, often creates millions of small files. The LH must constantly run background jobs to consolidate these files into larger, optimally-sized files (128MB to 512MB). This dramatically reduces the overhead required for the query engine to read the metadata manifests and minimizes expensive API calls to the object storage. Failure to compact files will cripple LH query performance and escalate transaction costs.

Partitioning and Clustering: While the DW automates internal clustering, the LH requires explicit design. Partitioning (e.g., by date or country) is essential for efficient pruning. However, excessively narrow partitioning (e.g., by hour and user ID) leads to partition explosion—millions of small, empty directories—and should be avoided. For fine-grained optimization, use Z-Ordering (or similar techniques) on frequently filtered columns to ensure data blocks containing relevant values are physically stored close together.

Statistics Collection: Ensure your compute engines (Spark, Trino, etc.) run regular jobs to collect and update column statistics (min/max values, distinct counts). The query optimizer relies heavily on these statistics to make intelligent decisions about which files to skip or which join strategies to use.

8.2 Cost Governance

While the LH's storage costs are low, the decoupled nature introduces new avenues for cost leakage, primarily in compute and data transfer.

Egress Cost Monitoring: The most significant source of unpredictable cost in a cloud LH is data egress. This is the fee charged by the cloud provider when data leaves the storage region. Design your architecture to ensure all primary compute (Spark, query engines) is co-located in the same cloud and region as your object storage (S3, ADLS, GCS) to minimize this cost.

Effective Workload Management: The DW often excels here because it manages compute (auto-suspending clusters when idle) as a fully integrated service. In the decoupled LH, you must explicitly manage and auto-scale your compute clusters (e.g., Spark clusters or Trino coordinators). Implement aggressive auto-suspension policies to shut down compute resources after short periods of inactivity, preventing wasteful consumption.

Compute vs. Storage Trade-off: Recognize that optimizing the LH often means increasing compute time (e.g., running compaction jobs) to save on future, more frequent query compute time and API costs. This is a deliberate, necessary investment: Spend a little compute time upfront on maintenance to save a lot of money on query execution later.

9. Some FAQs

A sophisticated understanding of data architecture requires directly confronting and clarifying the most common misconceptions. We address these frequently asked questions to solidify the mental model for the reader.

9.1 Is the Data Lakehouse a replacement for a Data Warehouse?

The technical answer is No, not entirely, but it is a formidable challenger to the DW's monopoly on reliability. The LH has achieved feature parity with the DW in terms of ACID transactions, schema management, and governance via open table formats like Iceberg. This makes the LH the superior choice for unifying batch, streaming, and ML/AI workloads at petabyte scale and minimal cost. However, the DW still holds an advantage in a narrow, specific domain: high-concurrency, sub-second BI query serving. For organizations prioritizing only that single, high-SLA workload and willing to pay the premium for simplicity, the DW remains justifiable. For every other analytical need, the LH is the more future-proof and cost-effective architectural foundation.

9.2 Can I use Snowflake/Databricks/BigQuery as a Lakehouse?

This is a subtle question about terminology versus architecture. Yes, and No.

Databricks (using Delta Lake, its open format) pioneered the Lakehouse concept and is a native Lakehouse platform that sits atop open storage. The architecture perfectly aligns with the decoupled Lakehouse definition.

Snowflake and BigQuery are primarily Data Warehouses. They excel through their proprietary, integrated storage and compute. However, they are adapting. Snowflake now supports features to read and manage data directly on an external S3/ADLS bucket (an external table), moving toward a Lakehouse-like capability. Similarly, BigQuery can query external data. The key distinction remains: when you fully leverage these platforms, you are using their proprietary storage, which forfeits the openness and portability that define the true Data Lakehouse philosophy. They are using Lakehouse features, but not fully adopting the open Lakehouse architecture.

9.3 How do Data Lakehouses handle high concurrency reporting compared to Data Warehouses?

The DW has a clear architectural advantage for high concurrency: its tightly coupled, proprietary storage is optimized to serve thousands of concurrent queries by design. The LH requires more explicit work. While modern query engines (Trino, Spark) can deliver competitive speed for analytical queries, handling high-concurrency BI serving demands a highly tuned environment.

The pragmatic solution is to implement the Unified Hybrid Architecture (Section 5). The LH handles the large, complex transformations cheaply, but the final, highly aggregated Gold consumption layer is copied to a high-performance DW which is then used exclusively for high-concurrency dashboards. The LH is fast; the DW is still faster for specific, high-concurrency BI serving.

10. Conclusion

The debate between the Data Warehouse and the Data Lakehouse is not merely technical; it is a question of integrated simplicity versus strategic freedom. Having systematically deconstructed the core architectural differences and feature sets, we can now offer a definitive final perspective.

The fundamental thesis is that the LH fundamentally challenges the DW's historical monopoly on reliability and governance. The breakthrough is the open table format layer (Apache Iceberg, Delta Lake), which brings essential capabilities like ACID transactions, schema evolution, and time travel to low-cost cloud object storage. While the DW provides integrated performance and simpler out-of-the-box security at a premium cost, the LH provides massive scale, flexibility for multi-structured data, and the crucial benefit of zero vendor lock-in.

For the vast majority of modern enterprises, the architectural decision should lean toward the Data Lakehouse as the primary strategic foundation.

Prioritize the LH If: Your data volumes are expected to scale rapidly (petabytes), your workflows include complex AI/ML feature engineering, or your enterprise demands a clear exit strategy from proprietary platforms. The LH architecture, when correctly governed and maintained, offers a demonstrably lower total cost of ownership at scale.

Prioritize the DW If: Your only mission is high-concurrency, low-latency SQL serving for established, structured BI reports, and your organization is willing to accept the high, fixed costs and proprietary constraints that come with it.

The most robust and pragmatic solution for large organizations remains the unified hybrid architecture. Use the Data Lakehouse to manage the complex, high-volume, and raw data layers (Bronze/Silver), reaping the benefits of its low-cost storage and feature flexibility. Use the Data Warehouse only as a high-performance serving layer for the final, aggregated Gold data, leveraging its integrated speed precisely where sub-second latency matters most.

Ready to build your Data Lakehouse? OLake helps you replicate data from operational databases directly to Apache Iceberg tables with CDC capabilities, providing the foundation for a modern lakehouse architecture. Check out the GitHub repository and join the Slack community to get started.

OLake

Achieve 5x speed data replication to Lakehouse format with OLake, our open source platform for efficient, quick and scalable big data ingestion for real-time analytics.