How to Compact Apache Iceberg Tables: Small Files + Automation with Apache Amoro

1. Introduction

The modern lakehouse promises the flexibility of data lakes with the performance of data warehouses. But there's a hidden operational challenge that can silently degrade your entire analytics platform: file fragmentation. This section explores why building a lakehouse is easy, but keeping it fast requires active maintenance.

1.1. Data Lakes Are Easy to Write, Hard to Read

One of the nicest things about building data lakes on object storage—whether it’s S3, GCS, or Azure Blob—is how easy it is for data producers. You just write your Parquet files, add them to your Iceberg table, and you’re done.

Because of this write-first, low-friction design, data lakes are incredibly appealing. Teams can stream data from Kafka, run CDC pipelines that capture every tiny change, or use Spark jobs that naturally output tons of files per partition. From the writer’s point of view, everything feels smooth and straightforward.

But over time, a quiet problem starts to show up: reading the data gets slower and slower. Queries that used to be almost instant start taking seconds, then minutes. Query planning—something that should be fast—begins taking longer than the query itself. Dashboards time out, users complain, and your “cheap and fast” lakehouse suddenly doesn’t feel either of those things.

And the underlying reason is simple: while writing lots of small files is super convenient, reading them is painfully inefficient. Each file—no matter how tiny—requires opening a connection, reading metadata, coordinating workers, and closing it again. That overhead adds up fast.

1.2. The Silent Killer: Fragmented Files

File fragmentation doesn't announce itself with error messages or alarms. Instead, it degrades performance gradually, making it easy to overlook until the problem becomes severe.

Here's what happens in a typical lakehouse over time:

Week 1: Your new Iceberg table has 500 optimally-sized files (256MB each). Queries are fast, planning is instant, and your team is thrilled with performance.

Month 1: Real-time ingestion runs 24/7, creating 1,000 new files daily. Now you have 30,000+ files. Queries are noticeably slower, but still acceptable.

Month 3: File count exceeds 100,000. Query planning takes 30-60 seconds. Some queries time out. Users start bypassing the lakehouse, going back to querying production databases directly—defeating the entire purpose of your data platform.

Month 6: After adding more streams, ingestion ramps to ~3,000 files/day. You now have 500,000+ files and the table is practically unusable. Metadata operations fail, time-travel queries crash, and you're spending more on S3 API calls than on compute. The lakehouse feels fundamentally broken.

This progression is inevitable without intervention. File fragmentation is the silent killer of lakehouse performance.

1.3. Why Compaction Has Become a Mandatory Dataset Operation

In traditional databases, maintenance happens automatically in the background. PostgreSQL runs VACUUM, MySQL optimizes tables, Oracle manages segments. Users rarely think about physical storage organization because the database handles it.

Data lakes operating on open table formats like Apache Iceberg don't have this luxury—at least not by default. You're responsible for table maintenance. Without it, your lakehouse degrades into an expensive, slow data graveyard.

Compaction is the most visible part of Iceberg table maintenance—along with manifest rewrites, snapshot expiration, and orphan file cleanup. Compaction has gone from “nice to have” to absolutely essential, and there are a few clear reasons why:

1. Real-time pipelines are the norm now - CDC, Kafka streams, and continuous ETL all generate lots of small files—there’s no way around it.

2. Cloud costs make inefficiency obvious - Every API call, byte scanned, and second of compute shows up on the bill. Small files = bigger bills.

3. Scale makes the problem unavoidable - What works fine at 100 GB breaks at 10 TB, and completely collapses at 1 PB.

1.4. Iceberg & Amoro as Solutions for Modern Lakehouses

Iceberg tracks every file, maintains detailed statistics, and supports atomic rewrites that don't disrupt concurrent readers or writers. The challenge? Iceberg gives you the tools, but you must orchestrate them. You need to:

- Monitor table health continuously

- Decide when compaction is needed

- Choose appropriate strategies

This operational complexity leads many organizations to build custom automation—or worse, neglect maintenance altogether.

Enter Apache Amoro (incubating): a lakehouse management system built specifically to solve this problem. Amoro provides self-optimizing capabilities that continuously monitor your Iceberg tables, automatically trigger compaction when needed, and maintain optimal table health without manual intervention.

2. What Causes the Small Files Problem?

Understanding the root causes of file fragmentation is essential for preventing and addressing it. This section examines the common workload patterns that inevitably produce small files and why they're so pervasive in modern data architectures.

2.1. Real Time Ingestion:

Real-time data ingestion is the primary culprit behind small file proliferation. Let's examine the most common patterns:

1. Change Data Capture (CDC): When you capture database changes from PostgreSQL, MySQL, or MongoDB, each transaction or batch of changes becomes a separate write to your Iceberg table. A busy production database processing thousands of transactions per second can generate millions of tiny files daily. For example, high-volume CDC streams producing thousands of changes per minute result in hundreds of new snapshots created every minute, each potentially writing small files.

2. Kafka Streaming: Flink or Spark Streaming jobs reading from Kafka typically commit data at regular intervals (every minute, every 5 minutes, or after N records). Each checkpoint creates new files. With default configurations, a single streaming job can produce 10,000-50,000 files per day.

3. Micro-Batch Processing: Even "batch" jobs behave like streaming when run frequently. Organizations running hourly ETL jobs across hundreds of tables create constant file churn. Each run adds new files without consolidating old ones.

This isn't hypothetical. Organizations running CDC or streaming workloads on Iceberg face this exact problem: file counts grow exponentially, query performance degrades, and costs spiral out of control.

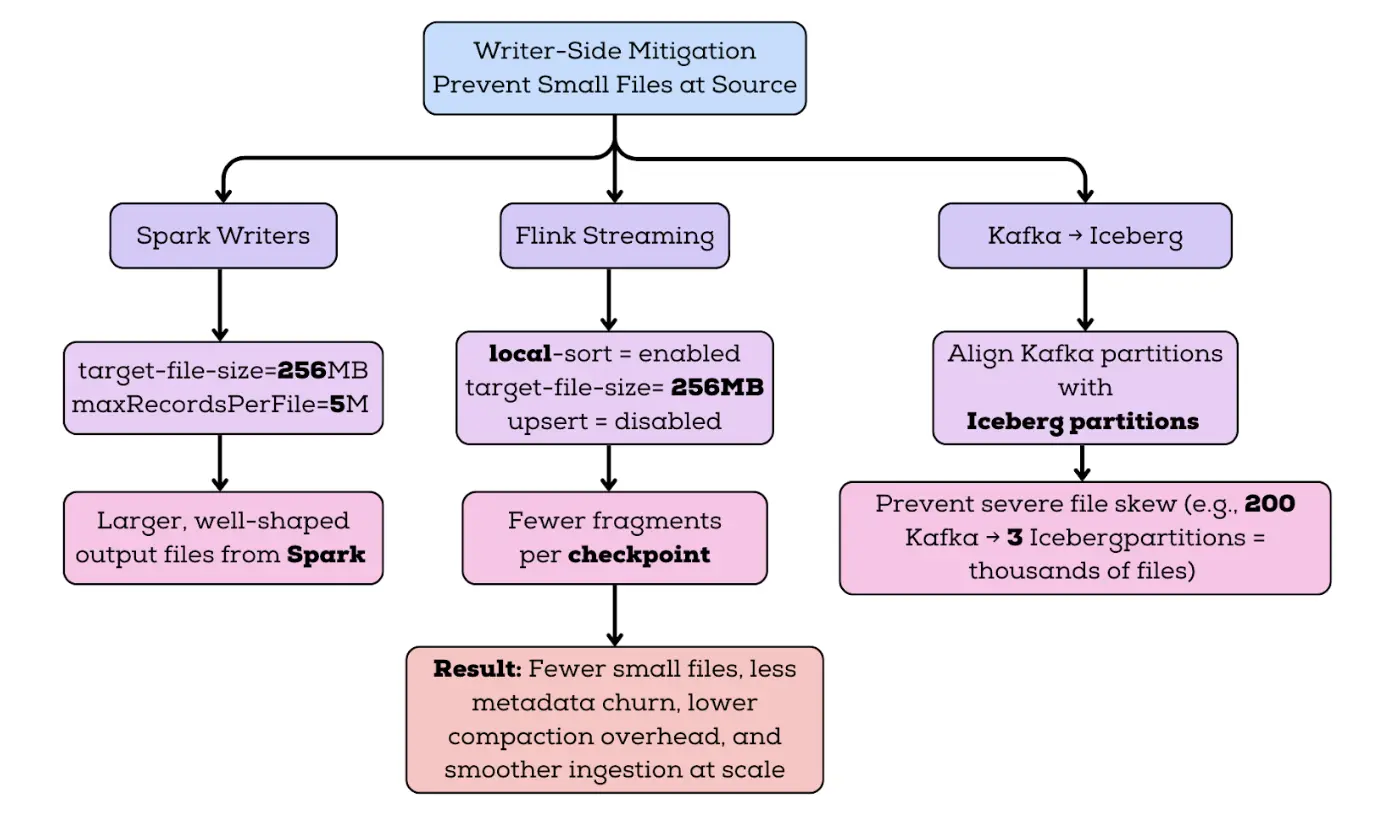

2.2. Distributed Writers Splitting Data Into Too Many Files:

Distributed processing frameworks like Spark and Flink parallelize work across many tasks. Each task writes independently, creating separate files. Without proper configuration, this parallelism creates excessive fragmentation.

Spark's Behavior: It uses 200 shuffle partitions by default (spark.sql.shuffle.partitions=200). When writing to an Iceberg table partitioned by date (eg. today's date), Spark creates up to 200 files for that single partition in a single job run.

Compounding with Table Partitions: If your table is partitioned by high-cardinality columns (user_id, device_id, region), the problem multiplies:

- 200 Spark tasks

- 1,000 table partitions with data

- Worst case: 200,000 files per job

Flink's Parallelism: Flink's parallelism setting determines task count. With parallelism of 50 and hourly checkpoints, that's 50 new files per hour per partition with data.

Why Writers Don't Consolidate: Distributed writers focus on throughput and fault tolerance, not optimal file sizes. Consolidating files during write time would create bottlenecks and reduce parallelism. The expectation is that compaction happens as a separate maintenance operation.

2.3. Frequent Updates & Deletes → Too Many Delete Files

Apache Iceberg V2 introduced delete files to enable efficient updates and deletes without rewriting entire data files. This is a powerful feature but creates a new dimension of the small files problem.

How Delete Files Work:

- Position Deletes: Mark specific rows as deleted by file path and row number

- Equality Deletes: Mark rows as deleted by column values

The Problem with Delete Files: Each UPDATE or DELETE operation can create new delete files. In CDC scenarios where you're continuously updating a table to mirror a production database, delete files accumulate rapidly:

- Every update = 1 equality delete + 1 insert (new data file)

- 1,000 updates/second = 86.4 million delete files per day

Read Amplification: At query time, engines must:

- Read data files

- Read position delete files

- Read equality delete files

- Perform joins to filter deleted rows

- Return final results

With thousands of delete files, this "merge-on-read" operation becomes expensive. Research shows query performance can degrade by 50% or more when delete files constitute 20% of total files. Major query engines like Snowflake's external Iceberg support only handle position deletes, while Databricks doesn't support reading delete files at all.

2.4. Unoptimized Partitioning

Poor partitioning strategies exacerbate the small files problem:

Over-Partitioning: Partitioning by high-cardinality columns (customer_id with millions of customers) creates an explosion of partitions. Even if each partition has few files, the total file count becomes unmanageable.

Under-Partitioning: Not partitioning or using only low-cardinality partitioning (year) puts all files in few partitions, making compaction expensive and reducing query pruning benefits.

Partitioning Mismatched to Queries: Partitioning by one dimension (date) when queries filter on another (region) forces full table scans, wasting resources regardless of file count.

Hidden Partitioning Complexity: Iceberg supports hidden partitioning (partition transformations like days(timestamp)), but improper use can create unexpected partition counts.

3. Why Small Files Are Bad

Understanding why small files hurt performance is crucial for justifying the investment in compaction infrastructure.

3.1. Query Engines Become Extremely Slow

Before a query engine can read data, it must plan the query. Planning involves:

- Reading the Iceberg metadata.json file

- Loading the manifest list (index of manifest files)

- Reading each manifest file (lists of actual data files)

- Building a query execution plan

With many files, this hierarchy explodes for instance:

- 10,000 files: ~50 manifest files, ~5MB total metadata, planning takes 1-2 seconds

- 100,000 files: ~500 manifest files, ~50MB total metadata, planning takes 10-30 seconds

- 1,000,000 files: ~5,000 manifest files, ~500MB total metadata, planning takes 2-10 minutes

Why This Matters: Query planning is synchronous and single-threaded in many engines. While planning, the cluster does nothing productive. Users wait. Dashboards timeout. Interactive analytics becomes impossible.

3.2. Poor Data Skipping & Predicate Pushdown

Modern query engines use statistics to skip reading irrelevant data. Iceberg stores these statistics in manifests:

- Min/max values for each column

- Null counts

- Row counts

Data Skipping with Large Files:

SELECT * FROM events WHERE event_date = '2024-12-01' AND user_id = 12345;

- Engine reads manifests

- Finds files where

event_daterange includes 2024-12-01 ANDuser_idrange includes 12345 - Reads only matching files (maybe 5 out of 1,000) and skips 99% of data.

Data Skipping with Small Files:

- Each file has wider min/max ranges

- More files match the query predicate hence engine ends up reading a lot more data than necessary.

- Leads to taking more time to plan the query and read the data.

3.3. Higher Compute Costs

Too many small files make engines spend more time managing work than actually processing data.

Spark example:

- Spark distributes files across executors as tasks

- With 10,000 small files and 100 executors, each executor processes 100 tasks

- If your cluster costs $100/hour, and a job takes 2 hours instead of 1, you pay double. Run that job daily and you waste $3,000–$4,000 per month on just one pipeline.

3.4. The Impact on Object Storage and Catalog

Small files create cascading impacts across every component of the lakehouse architecture:

Object Storage (S3/GCS/Azure):

- Cloud providers charge per API request. Queries reading 100,000 files make 100,000+ GET requests, costing real money

- Storage overhead: Each file has metadata (filename, permissions, timestamps) consuming space beyond the actual data

Catalog Systems (Hive Metastore / Glue / Nessie):

- Catalogs store table metadata and snapshot information

- More files = larger metadata = slower catalog operations

The small files problem isn't just technical—it's operational and financial.

3.5. More Manifests & Snapshots

Every write to an Iceberg table creates a new snapshot. Each snapshot references manifest files listing all data files.

Snapshot Accumulation:

- Streaming job commits every minute = 1,440 snapshots/day = 43,200 snapshots/month

- Each snapshot has a manifest list + manifests

- Without expiration, metadata grows unbounded

Expensive Operations:

- Time Travel: Queries at old snapshots must traverse old manifests. With thousands of snapshots, finding the right one and loading its metadata is expensive.

- Snapshot Expiration: Removing old snapshots requires listing all files in expired snapshots, comparing against current files, and deleting orphans. With massive metadata, this takes hours.

4. How Iceberg Solves This: Compaction

4.1. How Iceberg compaction works internally

Regardless of whether you trigger it using Spark actions or SQL procedures, Iceberg compaction follows the same safe rewrite workflow.

1. Selecting eligible files

Iceberg doesn’t rewrite everything blindly. It first decides which files are eligible based on rules such as:

- file size relative to the target file size

- partition boundaries (only files within the same partition are rewritten together)

- if sort order is defined, Iceberg keeps rewrites consistent with that ordering behavior

- file formats don’t mix (Parquet stays with Parquet)

This partition constraint matters operationally: compaction is usually most efficient when partitions align with query filters and ingestion patterns, because you’re compacting exactly the slices that are most frequently scanned or most heavily fragmented.

2. Grouping files using a rewrite strategy

Once eligible files are selected, Iceberg groups them into rewrite units. This is where compaction strategies come into play.

3. Atomic commit via snapshots

After rewriting, Iceberg commits a new snapshot that references the new files instead of the old ones. Readers see a consistent view throughout, and after the commit they automatically see the optimized layout.

Old files are not immediately deleted; they stay referenced by older snapshots until you expire them. That’s why compaction temporarily increases storage footprint and why snapshot expiration is part of “real compaction,” not an optional afterthought.

4.2. Compaction strategies in Iceberg

When people talk about compaction in Iceberg, they often describe it as merge small files into bigger files. That’s true at a very high level, but it hides an important detail. Iceberg doesn’t just decide which files to rewrite — it also decides how to rewrite them.

That “how” is the compaction strategy, and it has a big impact on both write cost and read performance. Iceberg offers multiple strategies, each optimized for a different type of workload. Understanding these strategies helps explain why compaction sometimes feels cheap and invisible, and other times feels heavy but transformational.

1. Bin-pack compaction (the default and most common):

Bin-pack compaction is the simplest and most commonly used strategy in Iceberg. Its only goal is to fix file size. In real systems, continuous ingestion produces lots of small files, Bin-pack compaction takes these small files, groups them together, and rewrites them into fewer files that are closer to a target size, such as 256 MB.

What bin-pack does not do is just as important as what it does. It does not reorder rows, change clustering, or try to improve data locality beyond file size. Rows remain in whatever order they were originally written. The result is simply fewer, healthier files.

This simplicity is exactly why bin-pack is the default. It’s cheap, predictable, and safe to run frequently, even on actively written tables. For append-heavy workloads, CDC pipelines, and general-purpose tables where the main pain is “too many files,” bin-pack compaction is usually all you need.

2. Sort compaction:

Now lets consider an events table where almost every query filters by event_date or event_timestamp. Data arrives throughout the day from many producers, so within each file the rows are in a mostly random order.

Even after bin-pack compaction, each file still contains a wide range of timestamps. When a query asks for “last 2 hours of data,” it ends up scanning many files. This problem is tackled by sort compaction.

When sort compaction runs, Iceberg reads the data, sorts the rows by event_timestamp or whichever column we provide, and writes out new files at the target size. Each file now contains a much narrower time range. After sort compaction, one file might contain events from 10:00–10:05, another from 10:05–10:10 and so on depending on the column we provide for sorting.

Now, when a query filters on a specific time window, Iceberg can skip most files using min/max statistics. The query reads less data, launches fewer tasks, and finishes faster. This extra work costs more CPU and memory, but it changes how data is laid out on disk. Rows with similar values end up physically closer together, which makes min/max statistics more effective. Queries that filter on the sort columns can skip more data and scan fewer files.

Sort compaction is most useful when query patterns are well understood and stable. If most queries filter on the same columns, sorting by those columns can significantly improve read performance. You can think of sort compaction as a deliberate investment: higher rewrite cost now in exchange for faster, more predictable reads later.

3. Z-order compaction:

Now imagine a large analytical table used by many teams. Some queries filter by user_id, others by country, others by event_date, and many use combinations of these columns. There is no single “best” sort column.

If you sort only by event_date, queries filtering by user_id still scan a lot of data. If you sort by user_id, time-based queries suffer. Z-order compaction goes one step further. Instead of optimizing for a single column, it tries to improve locality across multiple columns at the same time. Rows that are close in any combination of the chosen columns tend to end up physically close on disk.

After Z-order compaction, rows for the same user tend to cluster together, rows for the same country tend to cluster together and rows from nearby timestamps tend to cluster together. No single query gets a perfectly sorted layout, but many different queries benefit enough to skip significant portions of data.

The upside is flexibility, Z-order compaction can significantly help exploratory and ad-hoc analytics, where query predicates vary and no single sort order dominates. The downside is cost, Z-order compaction is the most expensive strategy in terms of CPU, memory, and rewrite complexity. Because of that, Z-order is typically reserved for large analytical tables where read performance is critical and worth the extra maintenance overhead. It’s not something most teams run continuously on hot, frequently updated data.

4.3. Full compaction vs Incremental compaction

All the strategies above can be applied either broadly or narrowly. That distinction is what people mean by full vs incremental compaction.

1. Full compaction: maximum optimization, maximum blast radius

Full compaction rewrites everything in a table or everything in a large scope like many partitions. It produces the most aggressively optimized file layout and can be excellent after:

- a large backfill

- major schema, partition, or sort changes

- a period of severe fragmentation

- migrating a dataset into Iceberg from another format

When you rewrite broadly, you usually end up with the cleanest result: fewer files, more uniform sizes, and better scan behavior.

But the cost is equally broad. Full compaction can:

- consume heavy compute and I/O for hours on large datasets

- create large commits and increase commit contention with active writers

- increase temporary storage footprint significantly

- disrupt streaming ingestion if it overlaps with hot partitions

In practice, full compaction is best treated as a scheduled “maintenance window” type operation run during low traffic, or limited to cold partitions that are no longer being written.

A simple full rewrite looks like:

- SQL

- Spark

CALL catalog_name.system.rewrite_data_files(table => 'db.sample', options => map(...));

import org.apache.iceberg.actions.Actions

Actions.forTable(spark, "my_catalog.my_table")

.rewriteDataFiles()

.option("target-file-size-bytes", "268435456") // 256MB

.execute()

This is powerful, but if your ingestion is continuous, you usually don’t want to do this frequently.

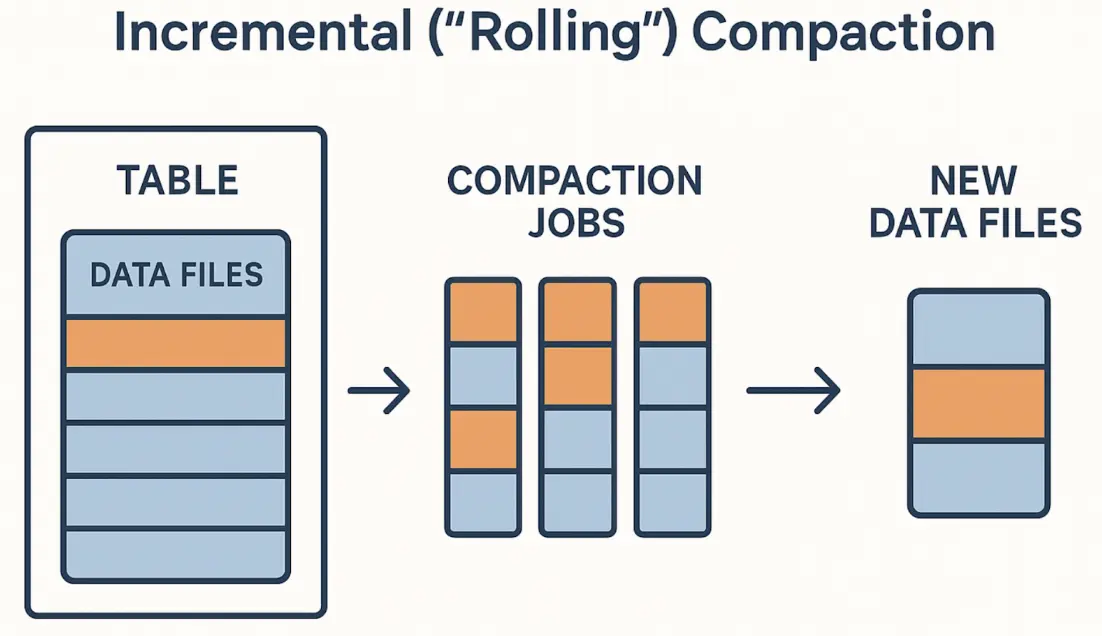

2. Incremental (rolling) compaction:

Incremental compaction accepts a simple truth: for large, continuously written tables, rewriting everything is usually unnecessary and operationally risky. Instead, incremental compaction rewrites parts of the table in smaller jobs that run frequently.

The practical benefits are huge:

- jobs complete in minutes rather than hours

- each job produces smaller commits (less conflict risk)

- failures are easier to recover from

- you can avoid compacting hot partitions where writers are active

- you spread I/O and compute cost across time rather than spiking

Incremental compaction is how most streaming/CDC Iceberg tables stay healthy long-term. The most common pattern is to compact cold partitions data slices that are no longer receiving writes. Another pattern is time-window compaction wherein we keep a rolling window of older data optimized while leaving the newest data alone until it stabilizes.

In practice, incremental compaction is done by scoping rewrites to specific partitions or time ranges, typically by running the rewrite procedure against selected subsets of the table based on operational rules (for example, compacting only older partitions):

- SQL

- Spark

CALL my_catalog.system.rewrite_data_files(

table => 'my_table',

options => map(

'rewrite-all','false',

'target-file-size-bytes','268435456'

)

);

import org.apache.iceberg.actions.Actions

Actions

.forTable(spark, "my_catalog.db.my_table")

.rewriteDataFiles()

// Scope compaction to cold partitions only

.filter("event_date < DATE '2026-01-01'")

// Target ~256 MB output files

.option("target-file-size-bytes", "268435456")

// Optional safety controls:

// .option("max-concurrent-file-group-rewrites", "4")

// .option("partial-progress.enabled", "true")

.execute()

The key ideas are:

- scope the rewrite (where) so you don’t collide with active writes

- tune concurrency so compaction doesn’t starve query workloads

- control rewrite parallelism and commit behavior so compaction does not overwhelm query workloads

Incremental compaction isn’t just “smaller compaction.” It’s a fundamentally different operational posture where we keep tables healthy continuously instead of waiting for degradation and doing big fixes.

Incremental Strategies commonly used are:

1. Cold-partition compaction is the safest default. You compact partitions that haven’t been written recently. This avoids conflicts with streaming writers and keeps the process predictable.

2. Time-window rolling compaction is common for time-series tables. You compact data in bounded slices (7 days, 14 days, 30 days), which produces consistent job sizes and predictable cost.

3. Threshold-based compaction triggers only when fragmentation crosses a boundary file count too high, average file size too low, delete-to-data ratio too large. This prevents unnecessary rewrites.

4. Predicate-scoped compaction uses Iceberg’s where filtering to target only the slices that matter. This is one of Iceberg’s most powerful operational features, because it lets you maintain only what needs it without rewriting what’s already healthy.

4.4. Why “I compacted, but it’s still slow” often comes down to delete files

In CDC-heavy workloads, the real pain isn’t always small data files. It’s delete files. Iceberg supports row-level deletes with position deletes and equality deletes. That avoids rewriting large data files for small changes, but it pushes work to reads: engines must reconcile base data with deletes.

Over time, delete files can accumulate and create serious read amplification. Even after you compact your data files into perfect 256MB blocks, you might still see poor performance if every scan must apply thousands of delete fragments.

This is why production maintenance often includes delete file rewrites in addition to data file compaction. In some stacks, you’ll merge delete files to reduce their count. In others, you’ll apply deletes by rewriting base data files so removed rows are physically eliminated.

If delete workload is high, treat “data compaction” and “delete compaction” as two separate maintenance loops.

Compaction rewrites data files, but it doesn’t delete old files immediately. Those old files remain referenced by older snapshots until you expire them. If you only compact data files but never expire snapshots, you’ll keep paying for storage, and planning may still degrade because metadata history keeps growing.

5. Enter Amoro: Automated Optimization for Iceberg

This section introduces Apache Amoro as the solution to operational complexity. While Iceberg provides the building blocks, Amoro provides the automation and intelligence to maintain table health continuously.

5.1. Architecture of Amoro

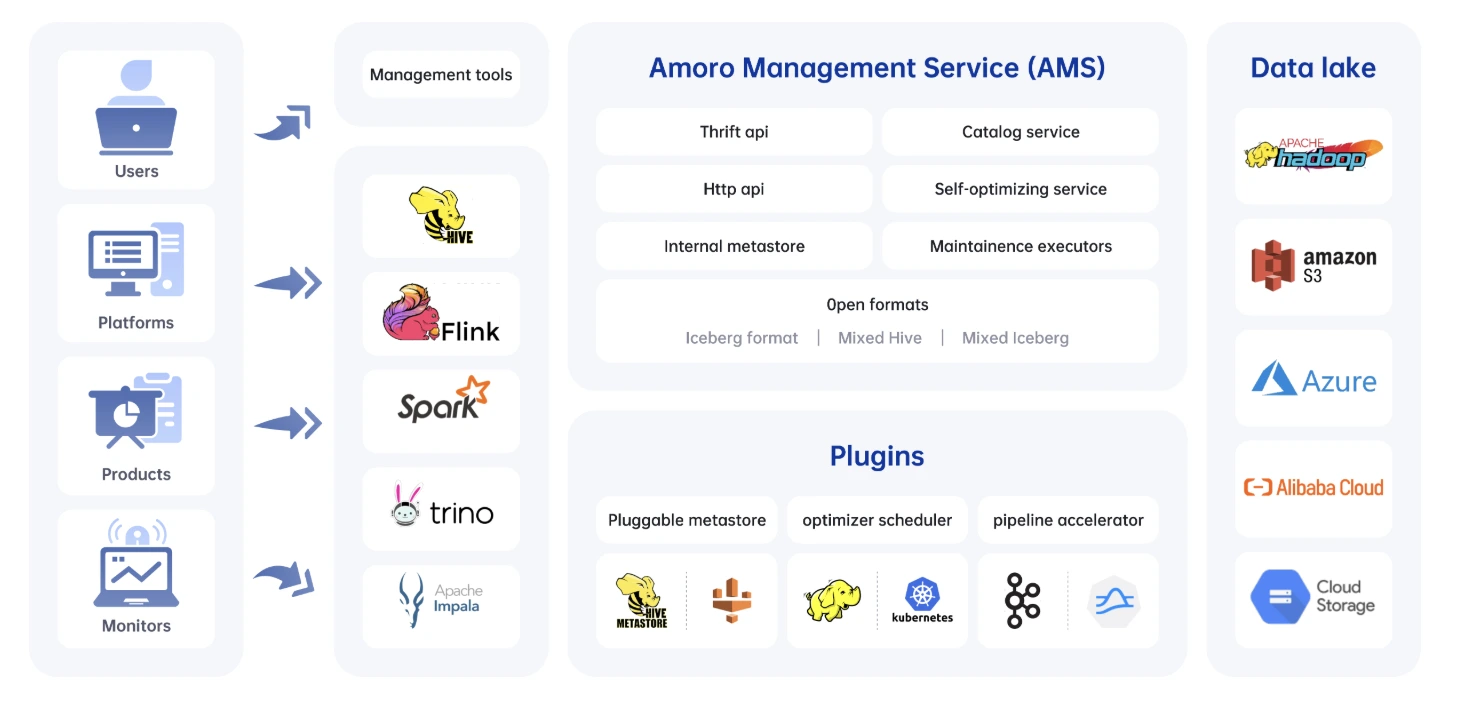

Amoro transforms Iceberg maintenance from a manual, engineer-driven process into a self-managing system.

The main components of Amoro are:

Amoro Management Service (AMS)

AMS is the brain of the system. It constantly watches over all registered Iceberg tables and evaluates their health—looking for things like too many small files, growing delete files, or bloated metadata. Based on what it finds, AMS automatically decides what needs to be optimized and when. It also manages the pool of optimizers, tracks their capacity, and exposes everything through a clean UI and a set of APIs so teams can monitor and control optimization activities without manual intervention.

Optimizers

Optimizers are the workers that actually perform the heavy lifting. They run the compaction jobs, merge delete files, rewrite manifests, and clean up snapshots. These workers are organized into resource groups so you can isolate workloads (e.g., separate streaming table optimization from large batch compaction). They scale independently from query engines, which means optimization does not affect query performance. AMS simply assigns tasks, and the optimizers execute them in a distributed, fault-tolerant manner.

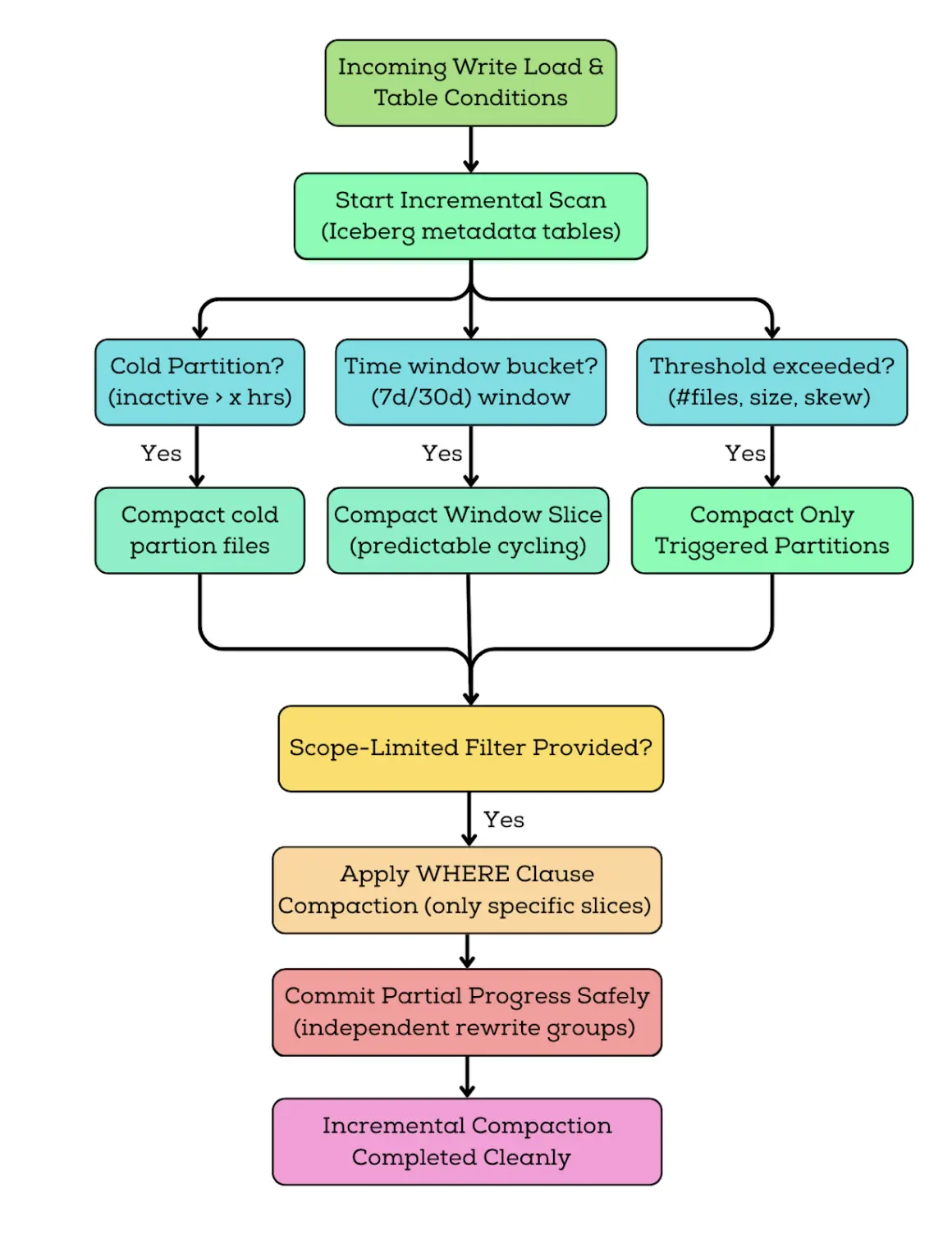

5.2. How Amoro Performs Continuous Small-File Optimization

Amoro keeps Iceberg tables healthy by running a continuous feedback loop. Every few seconds, AMS checks the state of your tables, decides what needs attention, and dispatches optimizers to fix problems without interrupting incoming writes.

1. Monitoring

Every 30–60 seconds, AMS scans the metadata of each registered table. It looks at file counts, average file size, delete-file buildup, and other health indicators. If a table starts accumulating too many small files, AMS immediately flags it.

2. Prioritization

Not all tables need help equally. AMS ranks tables based on their health score—tables with rapidly growing small files or high delete ratios automatically rise to the top. It also respects resource limits, so a heavily loaded cluster doesn’t get overwhelmed.

3. Scheduling

When a table needs work, AMS schedules an optimization task and assigns it to an available optimizer. It checks whether the table is actively receiving writes to avoid conflicts, and spreads tasks across optimizer groups to maintain balance and fairness.

4. Execution

Optimizers then perform the actual compaction. They read the small files, merge them into larger, efficient ones, write new data files, and commit a fresh snapshot back to the table. Once finished, they report results back to AMS.

5. Validation

AMS validates the commit, updates the table’s health score, and decides whether more passes are needed. If the table is healthy again, it returns to normal monitoring mode; if not, AMS continues scheduling tasks until the table reaches a stable state.

5.3. Minor vs Major vs Full Optimization Jobs

Amoro uses a two-tier optimization strategy that works similarly to how the JVM performs garbage collection. The idea is to keep tables healthy with frequent light operations, while occasionally running deeper optimizations when necessary.

Minor Optimization

Minor optimization runs very frequently typically every 5 to 15 minutes and focuses only on small “fragment” files that are under 16MB. It uses a fast bin-packing strategy to merge these tiny files, making it a lightweight process that finishes quickly and keeps write amplification low. The goal is simply to prevent heavy fragmentation before it grows. While it’s efficient and uses very few resources, minor optimization doesn’t completely reorganize the table, so the resulting layout is not perfectly optimal, and larger files remain untouched.

Major Optimization

Major optimization happens every few hours and targets a broader range of files, including medium-sized segment files in the 16MB–128MB range. Unlike the quick minor pass, major optimization performs a full compaction and can optionally apply sorting to improve clustering and query pruning. This job is more compute-intensive but creates a much cleaner and more efficient file layout. The trade-off is that it consumes more resources and therefore runs less frequently.

Full Optimization

Full optimization is the most intensive operation and runs only occasionally (usually daily or weekly depending on the workload). It rewrites entire partitions or even the full table, applying global sorting or Z-ordering to produce the highest possible query performance. Because it rewrites everything, it yields the most optimized structure but also has the highest cost, making it an infrequent but very impactful process.

5.4. Automatic Delete File Merging

Amoro handles delete files intelligently:

Detection

- Monitors delete file ratio (delete files / total files) to measure how much deletes affect the table.

- Tracks delete file sizes to catch when many small delete files start slowing down reads.

- Identifies partitions or tables with excessive delete files, marking them as candidates for cleanup before they impact performance.

Strategy Selection

- If delete_ratio < 10%:

Amoro performs simple consolidation, merging small delete files into fewer, larger ones so engines don’t waste time opening thousands of tiny delete files. - If delete_ratio < 30%:

Amoro performs partial application, rewriting only the data files that have accumulated the most deletes and hence reducing read-time overhead without rewriting everything. - Else (> 30%):

Amoro performs full delete application, rewriting all affected data files so that all delete files are applied and removed completely.

Result: Delete files never accumulate to problematic levels. Read performance stays optimal.

5.5. Automatic Metadata Organization

Beyond data files, Amoro also continuously maintains Iceberg’s metadata to keep planning fast and storage clean.

Manifest Optimization

- Automatically triggers manifest rewriting when the number of manifest files crosses configured thresholds, preventing metadata from exploding as tables grow.

- Consolidates fragmented manifests during major optimization cycles, grouping related metadata so engines can plan queries with fewer lookups.

- Ensures query planning stays fast by keeping the manifest layer compact, organized, and easy for engines to scan.

Snapshot Expiration

- Uses configurable retention policies (e.g., keep snapshots for 7 days or a fixed number of versions) to limit how much historical metadata accumulates.

- Automatically deletes expired snapshots to reduce metadata size and storage overhead.

- Coordinates with active optimization tasks to ensure no data or metadata files are removed while they are still needed for compaction or running queries.

- Performs orphan file cleanup, safely removing leftover files that are no longer referenced by any snapshot.

Under the hood, this maps to Iceberg procedures like rewrite_manifests, expire_snapshots, and remove_orphan_files to keep planning fast and storage clean.

The benefit is metadata stays clean, compact, and well-organized without manual maintenance. Even as tables scale to billions of rows and thousands of partitions, query planning stays consistently fast.

6. Conclusion

Compaction in Apache Iceberg is a core maintenance operation, but the right strategy depends on several factors including ingestion patterns, table size and growth rate, query latency requirements, delete behavior, orchestration design, and cloud storage cost constraints. In practice, the most robust production setups blend multiple techniques: continuous incremental compaction to prevent small-file buildup, periodic full table rewrites for deep optimization, metadata-driven triggers for intelligent scheduling, sorting during compaction to improve query performance, and regular snapshot expiration to keep storage lean. When these strategies are combined effectively, Iceberg evolves from a simple table format into a high-performance analytic engine capable of handling real-world streaming workloads and multi-terabyte–scale data pipelines with consistency and efficiency.

OLake

Achieve 5x speed data replication to Lakehouse format with OLake, our open source platform for efficient, quick and scalable big data ingestion for real-time analytics.